Drones – unmanned aerial vehicles – have gotten better and cheaper over the last several years. As they continue improving, they’re only going to become more important and more common in everyday life, and, as that happens, they’ll change everything about how we build and live within cities. But to understand where we’re going, we need to start with where we’re at today.

Super Selfie Sticks

Consumer drones are popular for aerial photography. Current generation models come with automated flight patterns for movie style videography. Features like follow me mode let users specify a subject (e.g. themselves) for the drone to follow, taking video like a flying camera operator.

The Return to Home function is another common feature. At takeoff, the drone drops a GPS pin and can navigate its way back if it loses contact with the remote control or its battery begins running low.

Gesture-based control is also becoming more common. Users control the drone via hand signals, allowing them to interact directly with the unit instead of through a remote control.

Flying Food Delivery

Commercially, the obvious application for drones is last-mile delivery.1 Walmart, Amazon, Alphabet, and UPS have all built or bought their way into drone delivery. Standalone outfits like Skydrop, Arialoop, and Flytrex are also trying to build independent businesses based on drone-delivery-as-a-service.

The business case for drones is faster, cheaper delivery. Air-based delivery routes could be more direct, and replacing delivery drivers with even partially-automated drones could reduce labor costs.2 There are, however, barriers to widespread adoption.

Battery range and weight constraints limit efficiency. Storms or even high winds can also keep drones grounded. There’s also a last foot delivery problem.

Getting a package from a drone and into a customer’s hands is complicated. Homes - even in relatively cookie-cutter American suburbs - aren’t entirely uniform. Some have pools, others have dogs or children running around - and that's all before dealing with everything that’s not a single-family home.

Operators are converging on a reverse crane machine approach as a partial solution. The drone lowers its package to the ground using a claw at the end of a cable.

This still leaves open the judgment call of picking a specific drop-off spot. For now, most operators still have a human in the loop for this last couple feet.

Killer Robots

Military drones were pioneered by U.S. forces in the mid-90’s. More recently, they’ve seen action in the Russo-Ukrainian War, where they’re used for both reconnaissance and targeted bombing.3

The Ukrainian R18 Octocopter, a purpose-built military drone, has a range of over 2 miles and carries a payload capable of killing a tank. Ukrainian defense forces have also retrofitted consumer drones for combat use. Some models are capable of carrying grenades and, at a couple thousand USD, they’re an inexpensive weapons platform relative to how much damage they can do.

Regulating the Sky

National aviation authorities regulate drone use. In the U.S, that responsibility falls on both NASA and the FAA.

NASA provides technical assistance to the FAA and is working to incorporate drones into the existing air traffic control system.

For its part, the FAA administers licenses and regulates use based on size, activity, and location. Consumer drones over 0.55lbs require registration and, starting in September of 2023, they’ll also have to support remote identification.

FAA regulations focus on being able to identify a drone’s pilot and hold them accountable if they break the rules. It’s unclear, though, that much preemptive enforcement takes place. Take, for example, the requirement that operators maintain line of sight when flying. It’s a rule, but there’s no one monitoring hobbyists piloting their drone from two blocks away in a random suburb.

Drone Tech of Tomorrow

Longer battery life, better flight performance, and a greater range of product features will make drones more useful for more things.

Consumer models could easily become extensions of our smartphones, similar to how smartwatches expanded on functionality we first learned to use on mobile. In the future, we might see camera drones as standard equipment for journalists doing on-the-ground reporting. Personal-use models that follow users around like video game familiars are conceivable as well.

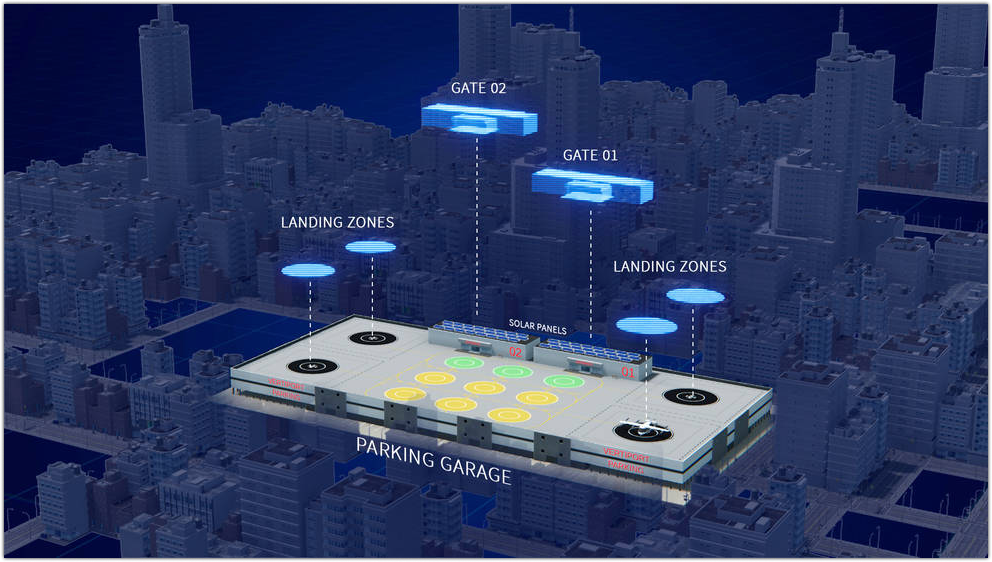

Commercial applications stand to have a bigger impact on urban development. If drone delivery proves profitable, it will change the way we build cities.

Landing / take-off pads could become standard for commercial real estate. Demarcated drop-off areas might become commonplace (i.e. mailboxes for drone delivery). How quickly any of this reorientation occurs, though, will depend on regulation.

The important factors, at least within the U.S., are how well authorities solve for collective action problems (e.g. right of way rules) and how much leeway they give operators to scale up. Once upon a time, private capital and public policy reshaped the U.S. for automobiles. For better or worse, we could get a repeat of that for drones.

Our regulatory regime will shape both commercial and recreational drone use - and how we reshape cities in response. But the single biggest factor preceding regulation is violence.

Everything’s Downstream of Violence

Retrofitting consumer drones for killing isn’t difficult. A drone with an explosive is a grenade launcher than can shoot around corners. On a long enough timeline, someone will use one for violence in the U.S.

Given that the existing regulatory regime is based on deterrence via the threat of punishment, there’s not much to stop a committed ideologue who’s indifferent to the consequences.

After a high-profile drone attack on U.S. soil, we can expect the regulatory response to be twofold: First, limitations on who can buy what types of drones. This will look something like a gun control regime and be meant to prevent the “Wrong People” from getting access to potentially dangerous drones. Second, we’ll see drone manufacturers being obliged to write regulations into code. This will be meant to make drones more difficult to use for violence.

Geofencing is an easy example of regulation in code. Most consumer drones can’t take off in or fly into restricted airspace. FAA regulations don’t currently require this – the onus is on the drone operator to follow the rules – but it wouldn’t be a giant leap for authorities to mandate geofencing and audit manufacturer code.

Other feature requirements could include remote kill switches enabling authorities to quickly ground a suspicious drone or any number of other built in back doors.

The bigger takeaway is that drones may give us the first major instance of regulation specified in code. As we deploy more semi–autonomous devices, code-level regulations could start to look like Asmiov’s Law of Robotics, limiting the uses and behaviors of autonomous devices moving throughout the physical world.

Urban Design in an Age of Drones

The rise of drones will impact what, where, and how we build things in our cities. Some of this will be physical, like landing pads on buildings. Some will be software based, like our geofenced no-fly zones. Others will involve hardware + software products that exist physically, but are built to interact with software.

When, where, and how quickly that happens, will depend on the challenges we encounter and the rules we write in response. Regardless of the specifics, drones are here to stay and the more useful they become, the more they’ll impact cities in turn.

Other commercial applications include videography (e.g. on movie sets) and agricultural use cases, but these won’t impact urban development as directly as delivery.

Even a drone that only required human intervention at drop-off could reduce labor costs on a per delivery basis.

For a full read on drones and modern warfare, check out Asianometry’s How Drones Disrupt Modern Warfare.

This is a great analysis