Homebuilding for the 21st Century

An Interview with Vikas Enti, co-founder and CEO at Reframe

Modular home construction is a perennial topic in the housing discourse. Offsite, factory-produced housing has been the main version of but maybe we can technology our way out of the problem for a while. And although I still see our various and sundry land use regulations as the immediate constraint on affordability, better methods of production definitely have a role to play.

To learn more about exactly that, I sat down with Vikas Enti, co-founder and CEO of Reframe, an up and coming home builder leading the revolution in modular construction. The following is a transcript of our conversation, lightly edited for readability; hope y’all enjoy.

Rethinking Home Construction

Jeff Fong: Let’s start with table stakes. What’s the difference between the types of homes you’re building and conventionally constructed ones?

Vikas Enti: Yeah, so let me start with what’s similar. We’re building homes that meet the same code standards. The way it gets lent against and transacted…it doesn’t have any distinction.

Where things get different is the advantages we get with factory built housing, in addition to being able to build these homes on a much, much faster timeline…with more cost certainty, more predictability…you’re also able to build to a much higher energy efficiency standard. A lot of this has to do with air tightness, which is a key function of energy efficiency.

For a home, it’s easy to apply the same amount of insulation in the factory; but to achieve air tightness, it’s a lot harder to do with on site construction, so the fact that the precision allows us to make sure that the homes we build exceed the energy efficiency requirements from air tightness so it directly translates to a home that ends up actually saving a lot more energy over time. That translates to cost savings for the owner from an energy efficiency standpoint.

The other benefit our customers get is the strength of these structures. We have to design our structures to be transportable, right? They’re transported on highways or trucks and have to withstand all the wind speeds there. They also have to be pickable by a crane, so the load ratings we’re designing our structures for typically exceed the wind load and snow load ratings of a typical home.

Our homes actually end up becoming a lot stronger, and we’re not deliberately designing to do that. We’re very optimal in how much material we use, but the way we’re modularizing the structures, we end up having additional walls, additional ceilings and floors that have to stack up. That all results in a home that’s not only significantly stronger, but also has much better sound isolation, so the comfort levels in these homes are much better.

The air tightness also results in a home that is not as susceptible to absorbing external pollutants. So if you had a wildfire outside or smoke outside, all the air that’s going in our units goes through what’s called an ERB, that’s an active ventilator with filters in it. So the actual air quality in our homes is much, much higher and better than a traditional site built home.

A Technologist Takes on Homebuilding

Jeff Fong: Can you say more about what you mean by the word module? What are the pieces that y’all are manufacturing and then assembling on site?

Vikas Enti: So for the Reframe approach, we’ve chosen to go with volumetric building blocks. We’ve broken a building down into full rooms, so what we’re shipping could be a collection of…a kitchen and a bathroom as one single box.

So we have the floor, the walls, the ceiling, all fully intact. Doesn’t need to have all sides. We have ways to transport them without all sides being built up. But we’re fitting out cabinets and appliances in the factory. We’re finishing the floors, the ceilings, all the electrical HVAC work also gets done in the factory. So we’re getting to a pretty high level of completion. Our goal is to at least complete 85% of the work in the factory. What ends up happening on the job site is you have these giant boxes brought down by flatbed trucks. You have a crane on site and the crane just picks up the box. It’s on the foundation, and you’re literally stacking a bunch of these boxes together.

And this conversation is timely. We just stacked our third project. So, our second customer project, third project to be fully done, was a three story apartment building in Somerville, Massachusetts. It took us three days to go from a foundation to a structure that was fully completed and dried in. And we’re driving efficiencies there, but yeah, like our building block is a volumetric module.

Jeff Fong: If we were on the factory floor I’m imagining these individual pieces would look like part of an Ikea showroom or a set from a TV sitcom?

Vikas Enti: Pretty much, it is surreal sometimes when the module gets to the final step in the factory and you walk in and you’re like…Oh, I’m in someone’s living room…and you’re still on the factory floor.

Jeff Fong: That’s cool, it almost sounds like pieces of a life size dollhouse.

Well, I noticed y’all build specific types of housing. I see multiplex, duplex, two-story, bungalow, and cottages. These are all what I would call missing middle. Is there specific thinking behind why y’all are focusing on these types of housing products?

Vikas Enti: Yeah, we’ve been pretty deliberate about focusing on missing middle as the core competency for the business.

When you sort of think about the market landscape today, there’s actually a good amount of housing that’s getting built in large scale single-family developments or in large scale multifamily. This is where all the big players are, but I think they’re still pretty mismatched on where people actually want to live and where we actually see existing services that can accommodate more housing; but the cost of building housing in those markets is incredibly high.

So, we’ve been focusing on missing middle housing for two reasons: one, we see a significant cost escalation. As an example, out here in Massachusetts, the greater Boston area, to build an infill lots current on-site construction costs range from $350 to $450 a square foot and that’s giving us enough headroom to actually bring our technology to market. And that’s pretty true across the country, where infill costs are sometimes twice as high.

The second reason we focused on this is, in our opinion, ripe for institutional capital over time, if you can establish that your delivery method actually allows you to get significant access to all these scattered sites and get cost efficiencies there.

The whole technology stack we built — with robotics for manufacturing and all the AI and algorithms on the design side — allows us to go after these infill lots with the same efficiency a production builder would get on their lots or for large multifamily. So there’s an intersection of where we saw market demand, but also where we saw a superior advantage with our approach.

A World Without Tape Measurers

Jeff Fong: Maybe that’s a good jumping off point, into y’alls process. I read that you’re using robotics not only to increase labor productivity, but also to decrease training time for new employees. Can you talk a bit about that? Are these bespoke internal tools or are you repurposing commonly used technology from types of manufacturing?

Vikas Enti: We use robotics today for automating framing of walls and ceilings, but we’re creating a roadmap to automate about 60-80% of tasks in the factory.

Our approach for Robotics has been very focused on maximizing the use of off-the-shelf hardware. The actual arm that you see is a standard industrial arm, you could pick any color and supplier you want to buy from. Our IP is what effectively ends up becoming the “hand” of the robot. So everything up to the wrist you can buy off the shelf; the hand is our custom design.

We also have this whole magnetic picturing technology that we’ve developed that allows us to … if you see the video on the website, the robot’s sort of framing studs onto this blank panel jig in the back. We use magnets to hold structures in place and that whole fixation technique is actually giving us significant cost advantages.

Our entire robotic work cell costs $200K and it’s 500 square feet in size. That’s a fraction of what other suppliers in the industry actually charge for these work cells. So we’ve got an advantage there. And using off the shelf hardware, custom end of arm tooling. And we use a 3D camera system and a significant amount of software that we developed that allows us to see these studs.

This reduces the need for us to have these massive conveyor lines that bring studs to the robot. Here, we just have a person dropping a pallet, but studs, the robot sees the studs and knows which ones to pick, and can directly go frame stuff. So we’ve been able to drive significant efficiencies there.

Jeff Fong: How much in-house software development have y’all done? I think I read something called pixels to parts?

Vikas Enti: It’s the backbone of our entire enterprise. We’re probably the only company in the world today where you have architects, carpenters, software engineers, roboticists, all eating lunch together. We’ve built a full stack approach, and so we’ve invested heavily in software. It actually precedes the manufacturing, it starts at the design step.

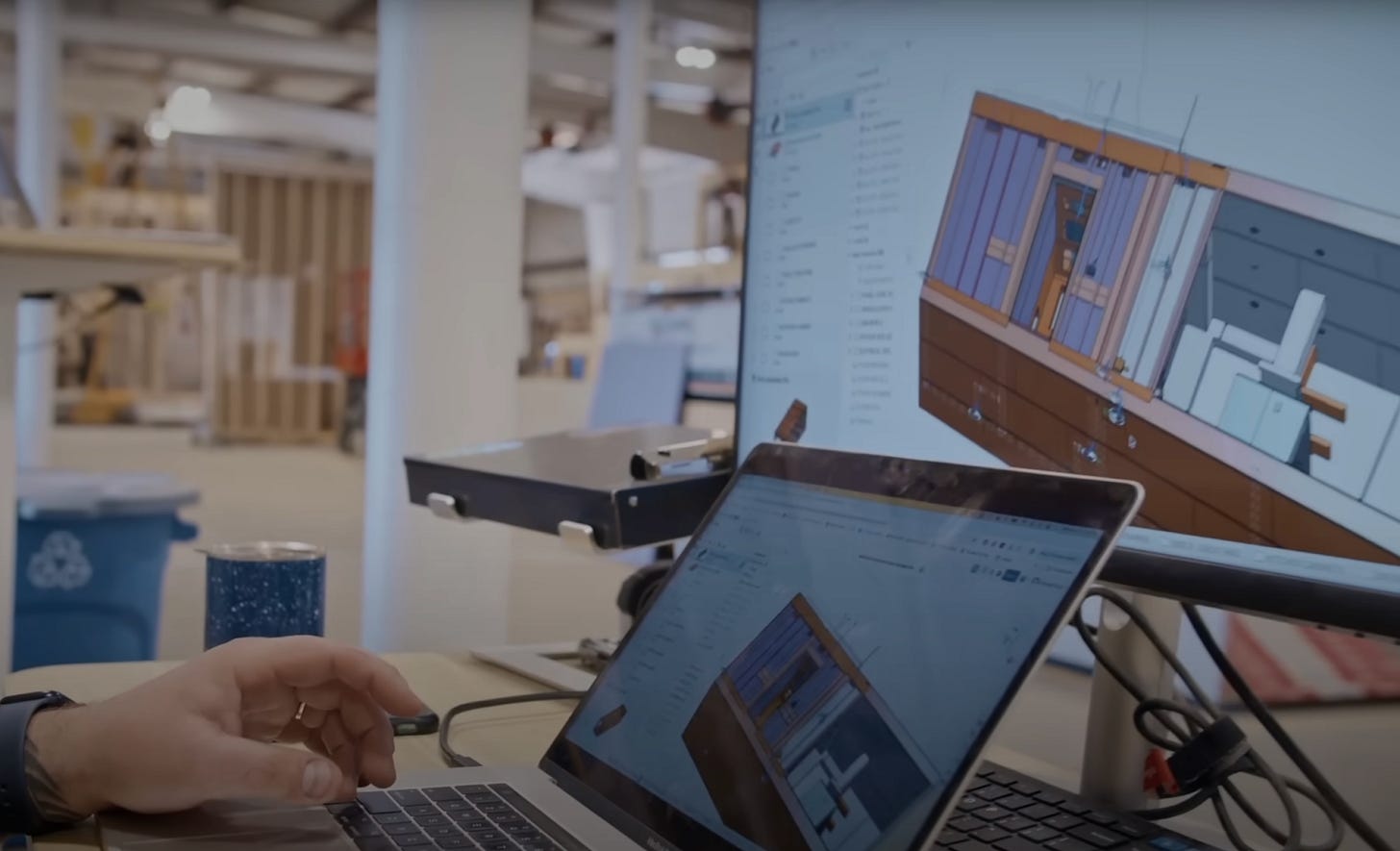

So even the way buildings are designed, we start work with the traditional work for the tool called Revit that most architects use, but very quickly jump into a mechanical CAD system called Onshape. And this is where we’ve been writing our custom software, inside Onshape, where we actually have simple things from “how do you automatically frame a full building?” all the way through more complex things, like, “how do you route pipes and wires automatically?”

So we’ve been building all these algorithms inside Onshape to make the design engineering process significantly faster. The place where we’ve already unlocked significant value, like, once you get to this high fidelity model…how do you automatically send instructions from that CAD model to the robot, to our CNC saws and routers, and also to people who were up-skilling (who are actually getting instructions off of an iPad).

And your IKEA analogy comes back to bear here again, which is the way we’ve sort of structured our whole process. The instructions from the CAD model kind of go in an order where it first sends cut instructions to our saw, and then our saw cuts lumber. But not only is it cutting it, it’s also printing instructions on it, and it’ll print barcodes. So for studs that are going to the robot, the barcodes help the robot understand what’s done in the recipe. But there are some walls the robot cannot frame today. These have to go to our manual framing station. Here we’ve printed locations of where exactly all the individual studs have to go line up, where we have the core holes, et cetera.

So the Build Team gets a kit of parts that already has instructions printed on it. Then they get supplemental instructions on an iPad, and they often tell us that this whole thing feels like them assembling Ikea furniture. They don’t need a tape measure anymore, right? We want to kill tape measures. We want to kill ladders. We want to kill chop saws. We want to take the stereotype of what a construction site needs to look like to a point where you’re getting pre-cut materials or parts coming together.

But to enable that feature, we have to do significantly more work on the 3D modeling side…to where we’re actually modeling every single wire, and then fixture, location, fastener locations….and then we’ve and we’ve made the cost of getting those instructions from the model to these endpoints, almost brought down to zero.

Productizing Construction

Jeff Fong: So it sounds like you’re really productizing the entire process bit-by-bit and saving humans for the hard parts. And did I hear correctly that within your software, you’re building an internal representation of every constituent piece of everything that you’re building? That’s got to significantly reduce waste, I’d imagine.

Vikas Enti: Absolutely. We’re already reducing a lot of waste with sheet goods. We get to nest any cuts we have to make, we get to plan material usage for the entire product or the project, versus just a single wall in front of you.

For optimizing lumber usage, we’re getting better there. I think we’ve had other challenges with lumber, just the quality of studs that we’re getting. So that’s been an active work in progress. But in principle, you’re right, because we’re effectively building a building three times: we build it 100% digitally, then we build them as modules in the factory, and then we get to assemble them on the job site.

We actually get three passes at getting this done versus the way it’s done in industry today, where you get line drawings from an architect and then you have a skilled trades person on the job site, figuring out, on the fly, exactly how they’re going to build that structure. They can’t really optimize beyond what’s in front of them. They get to build things once. So everything feels like a prototype. They get no efficiencies. Then you have all the waste from the material side and the labor hours that are not optimal.

We have reference products, right? So you mentioned the cottage house, the multiplex or duplex. We have a reference design, but that design means nothing until we can actually make it compliant for a given job site or a given site. We have to adjust dimensions sometimes to make it compliant with setbacks for zoning. Other times, you’ll have to change one wall to be more fire resilient because it has to meet building code requirements for separation and so on. There’s still work involved; this is not a mass production approach where you get to design one standard product and replicate it.

To truly be successful, we have to be able to customize these products to meet site conditions. And this has required us to invest in this whole pixel support [design] pipeline. Every single project has some variance, so we had to design this pipeline to make sure that the cost of customization actually goes down to zero for us, because the software is actually taking care of all the nitty gritties.

Modular Houses that Still Feel Like Homes

Jeff Fong: Your process is more to deal with local land use regulations and building code requirements — you’re not actually building custom homes, right?

Vikas Enti: Exactly, we’re not a custom home builder. Our customers are developers. We’re helping them maximize value for the parcels they have so they can realize their returns, build a lot more projects, and increase the supply of housing. For us to make this whole cycle time go really fast…the sooner we can get a building to be buildable by-right (where we’re skipping the whole zoning review process and going directly to permits) becomes a winning combination. To make that work, we need to be able to conform our designs to meet site conditions.

So the site is what we’re really obsessing over, but we’re not forgetting the living experience. We still believe in the Reframe living experience. People living in our homes get a vastly superior experience compared to the home next door. They’re more energy efficient, a lot quieter, a lot healthier, better materials, lower embodied carbon…like we baked a lot into our platform.

Jeff Fong: From the homeowners perspective, if you walked into a Reframe home, would you feel like you’re walking into a Reframe home?

Vikas Enti: Yeah, we’ve been very deliberate. The materials we’ve chosen, that the customers see and experience, that they’re very familiar, they’re no different. When people walk in, the usual reaction is, oh, I can’t believe this was built in a factory.People feel like it’s a normal home.

The apartment building we just built recently, breaks all notions. Like, this was built in a factory. It’s very hard for people to compare and contrast just from the sheer scale of it. But when you walk in, you find that we made design choices where we still have large open spaces.

We actually use three modules together that are connected to create the living room, dining room and the kitchen as one large open space. Which old school modular players were not able to do. Manufactured housing, which were the predecessors of trailer homes, tend to be just one or two boxes wide, and they have a very different design language and material choice that you can tell. Our stuff is pretty indistinguishable from materials you would use on the job site.

Reframe’s Business Model

Jeff Fong: A minute ago, you mentioned that your customers are actually developers, so you’re not interacting directly with the homeowner or the home buyer as a customer. Is that correct?

Vikas Enti: Yeah. So as a preferred go to market motion for us, we’ve been biasing more towards developers who can get us a multi-year pipeline. This allows us to actually plan for the required capacity. But the home we built last week was actually sold to a family.

It’s going to be a multi-generational living experience. This might be the only home where we actually know who’s going to be living in. The first home we built last year was built as a rental unit, but we never got to meet the occupant. All the other projects are designed without knowing who the end customer is. We’re not set up to be successful where we can provide a high touch experience to an end customer.

Jeff Fong: And if I remember correctly, Reframe is currently operating in Massachusetts and SoCal, is that right?

Vikas Enti: We’re fully operational here in Massachusetts. We’re setting up operations in SoCal. We’ve sold one project already for a rebuild in Altadena. In fact, I’ll be flying out there later today, and our goal is to set up a factory in SoCal by Q2 next year. We’re actively exploring factory sites for it.

Jeff Fong: And I also saw you referring to your production facilities as micro-factories. What’s the service area for one of these? If you set up a micro-factory in SoCal, is that serving all of San Diego?

Vikas Enti: Our preferred size is 50,000 square feet, which is about the size of a Garden Center at Home Depot, so relatively small. And for the service radius, our preferred radius is to be within 50-100 miles. That distance is actually more to do with us having better control and delivering a full stack experience, because we are the designer, manufacturer and on site installer. But from a logistics standpoint, I mean, we can ship anywhere. In fact, we’ll be shipping the first Altadena home from Massachusetts to California. It’s atypical, but the cost differentials are high enough that we can actually absorb the transportation costs to make this work as a pilot.

So there’s other examples. All Citizen M hotels in the US were built in Poland and ocean freighted over. There are companies building modules out in China and shipping them to the West Coast. There’s actually a pretty global supply chain around it, and it all just comes down to how much of a cost arbitrage you have. But our preferred approach, the business we want to be in, is one where micro-factories are local, so developers can build trust with the process.

We believe that’s a critical part that the industry was missing before that didn’t really allow it to spin the flywheel, to drive more demand. We want to make this experience very familiar. Not feel like a concept that people are trying to take a risk on. Like, we go to Home Depot to buy stuff. We could show up at our factory, see what’s happening. Like you contract with us, you’re able to check it anytime you want to. You know that this is just a better way to build a home — not a remote, scary approach, just something that’s a lot more pragmatic and practical for a certain type of product.

Amazon Robotics to Modular Homebuilding

Jeff Fong: In the last few minutes I’d like to ask you a little bit about yourself. How did you get into co-founding a modular home startup? I think I remember that you have an Amazon background, but what was your jumping off point here?

Vikas Enti: I mean, the short version is, I became a dad. Up to that point, I had deployed over half a million robots at Amazon. After becoming a dad, a lot of my focus sort of shifted to like, am I applying my skills in the right way where it matters? to where my kids, when they’re teenagers, can look back and say my dad did that.

My focus lens at that point was, how do you think about reducing carbon emissions? So which industry can you go to? Housing and our homes are actually one of the biggest contributors to emissions. About 27% of all carbon emissions come from our homes. So it became a good starting point, but as I got deeper into it…it became pretty clear that the housing crisis and the climate crisis are so intertwined and that this is the biggest problem of our generation.

I was pretty equipped to build conviction that this is a problem to solve. The solution took another six months to get the first pass on building conviction for…what does it look like to change the process and sort of take a factory built approach? Why factories? We get to bend gravity here, we get to build the ceilings and walls before we have to build the floors.

And my own experience from Amazon was like, don’t automate an existing process. Take a step back, redefine the process, and then bring automation in. So the factories made sense. I got to really explore this thesis for about six months with the venture firm. The goal was to kill this thesis, and I just fell in love with it. By the end of it, I was like, yeah, this is what I want to be doing. Then I went and found Aaron and Felipe, my co-founders, to come on the journey, and here we are.

Jeff Fong: Any last thoughts, anything else that I didn’t ask, or that you would want folks to know about reframe or what y’all are doing.

Vikas Enti: Quite simply, our whole mission is to build resilient homes that are attainable for everyone. People have gotten savvy about energy efficient homes, but they really aren’t thinking beyond energy efficiency. Given everything we’ve learned from the LA wildfires, what’s happening with tornado damage in St Louis, and wind damage from hurricanes in North Carolina… I think we need to build homes to a higher standard.

We want customers and stakeholders to actually demand that. Demand building codes, to actually adapt to what the changing world looks like.

Jeff Fong: Awesome. Well, that’s all I have for you this morning. Thank you for taking the time Vikas.

In business, as in life, timing is everything. And, given the times, the growing number of modular developers makes all the sense in the world to me. Over the last ten years the housing crisis has reached sufficient proportions to launch an entire political movement and the need for any and all solutions to address the millstone around society’s neck could not be greater. Moreover, the current administration’s immigration and tariff policies mean there’s never been greater need for productivity improvements in the construction sector.

There’s a regulatory angle here as well. Reframe, and other players in the space, specialize in missing middle types of housing products. These are housing typologies that we’re only now beginning to re-legalize in communities across the country. Some have pointed out that legalization doesn’t automatically produce new housing and while that’s true, I remain unworried. If we make the market for missing middle possible, entrepreneurs like Vikas will make it real.

Love this!

Resiliency to environmental conditions was definitely a piece of the puzzle missing from the classic “manufactured home“ paradigm.

I see that some municipal property appraisers still categorize manufactured homes as “mobile homes.“ This mischaracterization brings to mind a memorable quote from a dear old aunt, “tornadoes are attracted to trailer parks.“

With regard to popular demand for modular construction, the distinction between the classical conception of a mobile home and the modern reality of resilient modular construction is crucial.

It should be cost-effective to purchase or lease a lot with an obsolete “Doublewide“, and replace it with a durable manufactured home.