Robo-Taxis Are Finally a Thing (Kind of)

Where we're at, where we're going, and when we might eventually get there

Autonomous Vehicles (AVs) have been in the news as of late, mostly for pissing off San Franciscans. Over the course of a decade, we’ve gone from “AVs will replace human drivers tomorrow” to “all of it was always just vaporware” before settling on “it works…kinda”.

As we continue along the hype cycle, we’re going to start seeing exactly how good the tech really is and, more importantly, how people are going to react to sharing the streets with robots on four wheels.

How AVs Work (And Also How They Don’t)

AVs use lidar, radar, and cameras to see the world around them, but they don’t process everything about their environment in real time. Each vehicle has a pre-loaded model of its service area and knows the dimensions of every inch of road it’s going to drive ahead of time. These models also include traffic rules relevant to the service area. Things a human would have to read on posted signage, an AV just knows.

They even know specific local rules that wouldn’t necessarily be posted via signage. For instance, this example from Waymo’s blog:

…in San Francisco there are special areas called Safety Zones where buses and streetcars drop off and pick up passengers. If there is a bus stopped near a Safety Zone and it is not otherwise signed, it’s illegal for a car to drive more than 10 mph past the bus. We’re encoding Safety Zones into our map as a base layer, which helps ensure we are abiding by local laws.

Encoding all this context isn’t easy, though. It's why we don’t have AVs that know everything there is to know about driving everywhere in the U.S.

As of today, AVs as vehicles-for-hire can’t take you from San Francisco to Los Angeles, or operate anywhere outside existing service areas at all. The tech can’t abstract driving as a skill into new environments as well as a human can (yet).

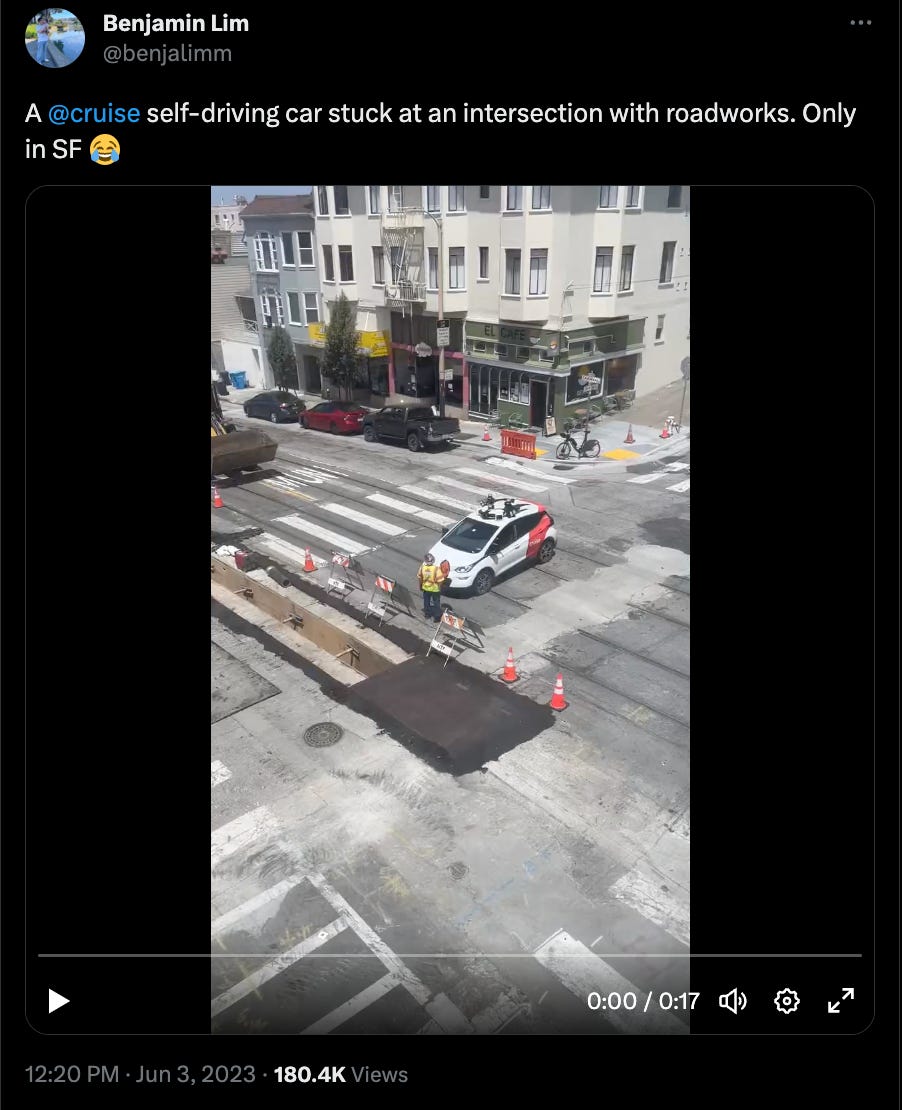

In the same vein, AVs don’t deal well with situational novelty. Reports of AVs slamming the breaks in response to plastic bags wafting across the road come to mind. The tech can tell when there’s an object in its path, but can’t differentiate between something solid it should stop for versus a floating piece of trash that it can (and should) drive right through.

On the flip side, AV companies report lower collision rates as compared to human drivers. They point out that AVs never get tired, drunk, or distracted, which is true, if somewhat misleading.

The failure mode for an AV whenever it encounters a situation it doesn’t understand is to stop and call for help. It sits wherever it’s run into an issue – blocking traffic – until a human operator comes to drive it away. So while it may be true that on the specific metric of collisions AVs get better grades, the fact that they get to press pause and call for help means it isn’t an apples-to-apples comparison.

It's also debatable whether fewer collisions mean AVs are categorically safer (the intended subtext). If an AV were to freeze and block emergency vehicles, that might constitute a safety issue even if no collision is involved.

The Business of Autonomous Vehicles

As of today, there are three main U.S. based robo-taxi companies: Waymo (owned by Alphabet), Cruise (owned by GM), and Zoox (owned by Amazon). All three are rolling out AVs on existing ride-hailing platforms and/or on their own AV-only platforms.

Deploying AVs as app-based vehicles-for-hire reduces the technical problem-space. It lets companies dictate when, where, and under what conditions their vehicles operate. Until the technology gets smarter, they're able to keep the task relatively simpler.

Deploying AVs on ride-hailing platforms also sets up operators to monetize in multiple ways. Amazon could bundle Zoox service into prime memberships. Alphabet could repurpose rider data for marketing.

There’s also value these services can extract from the data that individual AVs produce. It'll be similar to the type of information that Alphabet gleans from Maps and Waze, but even richer because AVs constantly scan everything around them as they drive.

The Political Economy of Robo-Taxis

Regulating AVs is a state-level prerogative. In California, for example, the DMV (for AV tech) and CPUC (for vehicles-for-hire) are the relevant agencies.

State-level oversight allows AV companies to get uniform regulations over large areas. It also offers insulation from popular pushback.

State administrative agencies are empowered by state legislatures and run by appointed bureaucrats. They don’t have direct constituents in the way that elected officials do. And because they function at the level of an entire state, they're less sensitive to hyper-local concerns; a couple hundred angry San Franciscans isn’t enough to directly move a state-level regulatory agency.

In the short term, this institutional arrangement gives AV companies a margin of error. Popular pushback has to move legislatures and/or governors’ offices enough to affect administrative bureaucrats.

Medium to long-term, the politics of AV tech is a waiting game. People get used to things. Human-operated vehicles are pretty dangerous, but we don’t bat an eye because it’s what we know. For better or worse, AV operators might be able to just wait out political resistance. The pot might be fine to simmer as long as the water never boils over.

People Do Weird Things in Cars

Technical problems and political landmines aside, there are operational headwinds.

Once upon a time, I worked the graveyard shift on Lyft's support line. I answered phone calls from 9 at night to 5 in the morning, so…trust me when I say that Weird Things Happen in Cars.

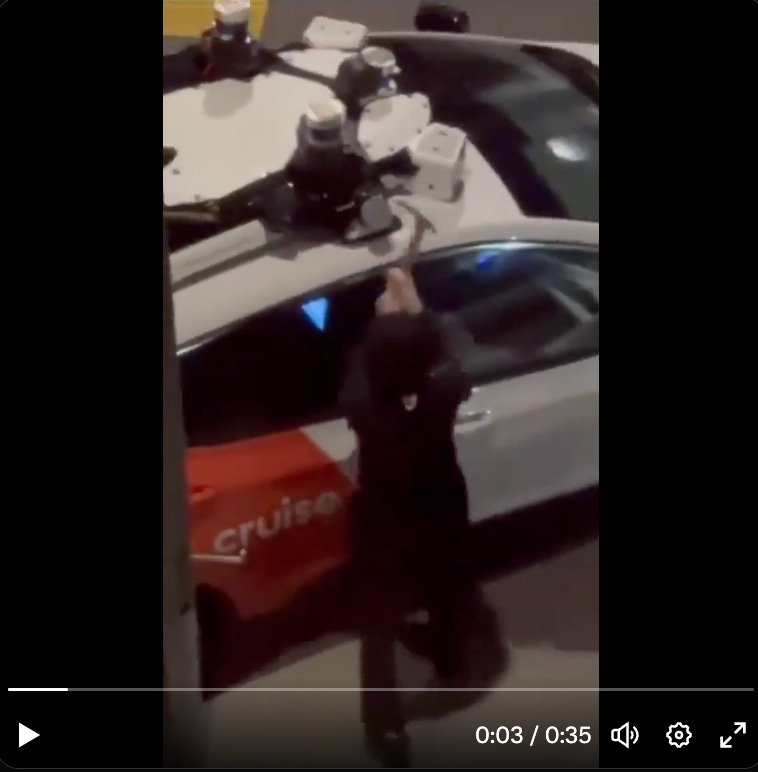

While a lot of these operational issues are super mundane (e.g. lost keys), sometimes, things get gnarly. Drunk people pass out (to the point that they can’t exit the vehicle). Angry people start fights. People have sex (already documented, naturally, in the case of AVs, because of course).

Now, none of these issues are insurmountable. Lyft and Uber have solved (or at least have standardized ways to remediate) anything that can go wrong. Solving them for a world without a human driver, though, will take some time–operational challenges are totally separate from improving the tech.

Farther Down the Road

Longer-term, ubiquitous AVs will reshape the way we live. In no particular order, here are some predictions.

Transportation

If AVs as vehicles-for-hire reach scale, they’ll reduce car ownership rates. Ride-hailing platforms used to claim they'd do this, but prices never got low enough to make them effective substitutes. With full automation, prices might actually get that low.

As the tech improves and operational problems get sorted, we’re also likely to see higher capacity, fixed-route transit. Whether this is in the form of autonomous public buses or Chariot-style van services (which was really just a Bay Area tech take on Latin American van networks) will depend on timing and politics. My best guess is that public sector unions will fight automating public bus routes, so a private sector implementation seems more likely.

Land Use

Folks once claimed AVs would lock in suburban sprawl. This was unequivocally wrong. AVs, however, could impact development patterns in other ways.

For starters, we might see parking garages repurposed as storage and maintenance centers. If platform-based AVs replace car ownership, people needing to park get swapped for AV operators needing to warehouse/refuel off-duty vehicles.

We may also see AV-specific signage. Today, visual markers indicating things like curbside loading zones are made for human drivers. In the future, we might physically annotate streets and buildings for the benefit of AVs. Imagine visual cues to help AVs tell the difference between curbs and the middle of the road. We might even create signage that’s only machine-readable. Our existing built environment was designed to make human-operated cars make sense. As AVs scale up, we’ll likely reshape the environment to better suit them as well.

Congestion Pricing

On the policy front, AVs might make every transit nerd’s favorite policy of congestion pricing possible. Congestion pricing is a surcharge paid by motorists based on traffic levels (i.e. surge pricing, but paid by everyone using a given section of roadway). Singapore is the classic example, but places like London have implemented it as well.

If platform based AVs replace car ownership, thereby creating a world where all vehicle trips are tracked and recorded, it becomes easy to tax the platforms running everything.

If we further imagine that platforms pass on the cost to riders (i.e. it costs more to take an AV during periods of peak congestion), congestion pricing would encourage riders to take mass transit. It might also induce the platforms to provide the autonomous vans or buses mentioned above as a way to serve more customers while reducing congestion (which, in this daydream, they’re obliged to pay for).

Final Thoughts

The next couple years are going to be wild. For those of us grizzled enough to remember a time before the internet, we’re on the cusp of a similar generational divide. AV operators already offer vehicle-for-hire services in San Francisco, Phoenix, and Austin. In short order, they’ll also deploy in cities like Seattle, San Diego, Miami, Nashville, Dallas, Houston, Raleigh, and more.

Anyone born today will grow up taking AVs for granted. How they think about transit systems, their relationship to car ownership, and what they default to as normal is going to be radically different from anyone already fully grown. For those of us living through the changes as adults, we might be cursed, but I’m fully confident that times are and will continue to be very interesting.