Inescapable Equilibrium?

Thoughts on the Boyd Institute's conversation with Dr. Cameron Murray

Earlier this week, I listened to a podcast and proceeded to lose my mind. Or at least enter into whatever dissociative state the DSM says causes time skips and seemingly spontaneous production of response pieces.

The episode in question was a Cameron Murray interview with William Miller and Peter Banks of the Boyd Institute. Cameron Murray does not believe that increasing housing supply can ever lower housing costs. Suffice to say I disagree with that viewpoint, but trying to grapple with what I can only describe as a macro-determinist worldview was fun, so I jotted down my thoughts in response.

What Crisis?

The Boyd Institute’s Peter Banks opens up the conversation with a straightforward question: Do you think there’s a housing crisis? Why do you think that way?

Murray responds:

If you think the housing crisis is something like the housing market behaving abnormally, then no.

A few minutes later, he goes on to say:

…to diagnose this as…something specific in the housing market has gone wrong, I think misunderstands the housing market.

I find this framing odd. No one I know in the YIMBY milieu is arguing that there’s some point at which housing markets (somewhere) worked and if we could only RETVRN to tradition we could restore what was lost.

At the highest level, the YIMBY problem statement is something like:

Housing prices are high (relative to people’s ability to pay) and this is bad (on grounds of justice, economic growth, environmental preservation, and more)

Prices are high because housing is scarce (in places of high-opportunity)

We can make housing less scarce (and therefore less expensive than would otherwise be the case) via different policy

As for the actual crisis, it’s the drag on the economy, effects on the environment, and disparate impacts on marginalized communities.

As for the YIMBY vision of a better world, realistically, we’re looking at moderating price-to-income ratios. Even outcomes where current price levels remain stable in high-opportunity metros, but we expanded the housing stock such that many, many more people could access them would be directionally correct.

Housing Markets According to Murray

Murray goes on to describe how prices get set in the housing market. He says (emphasis mine):

...if you want to fight economic forces you have to prevent trades that would otherwise occur because we are a rich society and rich societies like to spend money on things. That might be recreation, holidays, cars, but do you know what else? It’s houses. And unless you prevent people from trading those houses, you’re going to get to where the market price is, regardless of the overall quantity.

If I’m interpreting Dr. Murray correctly, he seems to be saying prices are determined by demand such that for any given quantity of supply we’ll always return to a constant price level.

While it’s not wrong that the wealthiest individuals in a housing market define the top of the distribution, demand from the super wealthy to live in any specific city is not infinite. Taking a step back, though, it seems like Murray just takes a very macro lens to everything.

At one point, Miller and Banks tee up a question with a hypothetical midwestern tech worker who would like to move to San Francisco. They imagine San Francisco built one more unit of housing, this midwesterner then moves to San Francisco freeing up a unit wherever in the midwest he’s just left and bob’s your uncle, downward pressure on prices.

Except Murray thinks not.

His riposte is that, sure, that could happen, but then that freed up midwestern unit just results in one less newly constructed midwestern unit. So at best, you’re moving things around. He also seems to be skeptical that allowing the market to spatially-reallocate our midwesterner to San Francisco is an improvement.

Granting his premise for a moment, I think removing material constraints and providing individuals with the widest set of choices about how they want to live their lives is good. To me, this scenario isn’t a question of trusting The Market with resource allocation. It’s about embracing a society where people have greater agency in a practical, material sense.

But also, I don’t believe we have to grant his premise.

There’s a robust literature on filtering. More specific to its mechanics, Michael Wiebe has a wonderfully accessible write-up on vacancy chains. Again, Murray doesn’t buy this, saying:

And if you go, Oh, … now there’s 20 dwellings, as in, you mean there are 20 dwellings at this location that the people living here didn’t buy off the plan of a different project at another location … If that’s your objective, that’s great … If you think we’ve suddenly got 20 more dwellings across the city more than the counterfactual, because there were no offsetting effects everywhere, then you’re wrong.

But this implies the existence of a self-equilibrating national housing market instead of a series of semi-interconnected regional housing markets, adjustments between which are full of friction and informational gaps.

So, I’m not convinced that tripling the amount of housing construction in San Francisco (or some other high-demand American City) results in every marginal rich person from everywhere else in the country descending upon the Bay Area. That would require rich households to have infinitely elastic location preferences (imagine someone in Boston constantly ready to outbid for SF housing if the price dips slightly). In reality, people have strong location preferences based on jobs, family, and networks that aren’t perfectly substitutable.

Murray’s version of a national housing market also seems to imply information is near-perfect and mobility is near-frictionless. The actual process of learning about housing in another city, coordinating a move, finding employment, etc. means the marginal buyer of new SF housing is much more likely to be someone already in the Bay Area trading up from existing housing stock.

Instead, I think the effect looks more like the top of the income distribution already in the region trading up to whatever the newest housing in the hottest location happens to be. That probably sounds strange to anyone actually from San Francisco and that would be because the city has built so little for such a long time that the richest neighborhoods today have been high-cost for fifty or more years at this point.1 In markets where building actually happens, the richest folks move around. For example, in Amarillo, Texas, the posh neighborhood changes every couple years as people with money want newer/better (it’s all very Veblen).2

Funnily enough, my last point accords with Murray’s description of the top of income distribution. The more money we have, the nicer things we want. The point of departure, again, is that he thinks the U.S. housing operates as a nation-wide, self-equilibrating market where building in one city versus another is just pushing peas around on a plate. I think the more relevant scale of analysis is within regional housing markets.

What’s Regulation Got to Do With It?

According to Murray, supply doesn’t really matter, therefore regulations that prevent supply in some specific place don’t matter much either. But this seems like an empirical question, so let’s turn to an example.

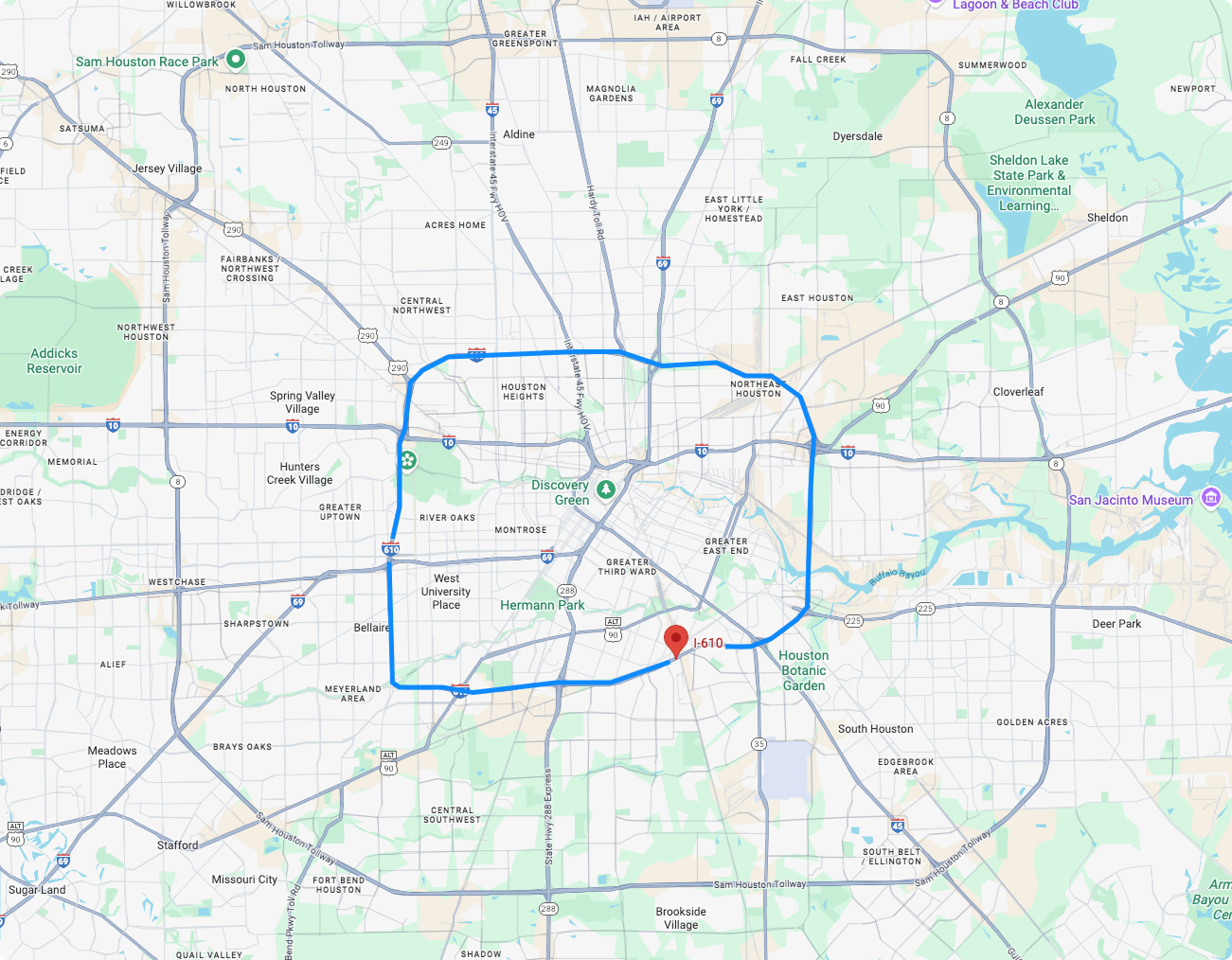

In 1998, the city of Houston significantly reduced minimum lot sizes in the area known as the inner loop. Previous to the reform, minimum lot sizes were set at 5,000 square feet; after the change, they were reduced to 1,400 square feet. In 2013, these changes were extended more widely. These reforms resulted in a boom of homebuilding, particularly of the kind the reform legalized — townhomes on small lots.

Research cited by Pew notes that the townhomes built by replacing an older single-family home (and subdividing the lots) had a “median assessed value of $340,000, considerably lower than the $545,000 median value of other new single-family homes in the city, and an amount that in 2020 was affordable for families earning at least 105% of the area’s median family income.”

This is roughly what I’d expect. Land costs are a major component of housing costs (in high-price metros, it could be on the order of 70% of total cost). When we allow denser development, i.e. we build such that more people can live on less land, we get relatively less expensive housing.

Time is Money

Getting more nuanced, Murray also dismisses the idea that timelines matter. In his view, being able to build faster doesn’t interact with price.

He goes on to provide an anecdote about a public housing provider in New South Wales with some properties that they decided to liquidate. According to Murray, they thought they were going to earn $400 million, the sale got delayed five years, and by the time they sold they ended up getting $710 million. He closes the anecdote by saying that if:

…the markets growing because the economy is growing and waiting pay is just as much as going and so it’s the change in the returns that stimulate those adjustments.

Which might be true, but not important?

Sure, land speculation is a thing.3 But there’s nothing that guarantees a particular return over some specific time horizon such that the developer turned speculator can plan accordingly. Miller even tried to pin him down on this, asking whether this logic would hold if the landowner acquired the land with leverage (i.e. had interest payments on debt to account for). Murray just kinda yadda-yaddas, saying that in general equilibrium it’s all the same and moves past the question.

But it matters.

Developers have heterogeneous capital costs. Changing the time cost of money changes the calculation differently for different actors. And, again, that cost is real.

A 2000 paper by Mayer and Sommerville, “Land Use Regulation and New Construction”, examined not just the relationship between regulation and price, but the link between regulation → how long it takes to produce new housing → the resulting impact that delay has on price.

Their findings were that discretionary permitting results in both a slower supply response and less new housing supplied overall…which increases prices relative to the counterfactual.4 To reach that conclusion, Mayer and Sommerville compared 44 different U.S. metros on the basis of how quickly (or not) their local land use systems allowed new housing starts. That’s relevant for our conversation because, and the authors make this point explicitly, there is no such thing as a national housing market (at least not in the U.S).5

American Land Use as Rent Extraction

My final point of consternation is with Murray’s account of land use planning. He says,

I think the best way to talk about town planning is it regulates where things go, not how quickly or how many there are.

I can’t speak with any authority on Australia, but to the extent Murray believes this is the case for U.S. land use, he’s factually incorrect.

The approval process is a major determinative factor in how quickly new housing can be built in the face of rising demand. And as for how many of something there is, in most places in the U.S., it’s illegal to build duplexes, therefore we don’t have many duplexes. Local land use regimes have an impact on the quantity of a great many different things from what I can see. Murray doesn’t stop there, though.

He continues:

Town planning exists in every city. It evolved everywhere for good reasons, right? There are noise, shadows, reflections, smells, vibrations, accessibility. The externality package of a city is enormous and we can litigate that through the courts the old fashioned way or we can just set some simple rules and go here if you comply with these do whatever you want and if you don’t we’re gonna have to have an argument.

As for this last bit, the answer is, again, largely no. American land use tools were not primarily invented to mitigate externalities, at least not in the sense I hope Murray means. They were created for the purposes of raising housing prices to segregate Americans along lines of class and race.

I really want to emphasize that this is not a controversial statement and I’m not attempting a 2015 twitter style everything-is-actually-about-racism dunk. The people behind what we now take for granted as standard land use policy were not hiding anything and this is well attested in books like The Color of Law, Stuck, and The Warmth of Other Suns.6

So, if we want to say that modern planning tools do not in fact raise prices we have to either hold the position that a) the originators of said tools — at least in the U.S. — were wrong in their understanding of policy or b) sometime in the last century, these tools underwent some change that rendered them benign.

Perhaps there’s an argument for the former, though I’ve yet to hear it. As for the latter, I’d need Murray to point out where on the timeline The Rings of Power went from implements of rent extraction to value neutral tools of modern life.

Murray’s Alternative

I found the entire conversation fascinating, but I wish I could have heard more about Murray’s alternatives for housing provision (I’ll have to go read his substack).

In keeping with his description of how housing markets work, his short answer for dealing with high prices was to prevent people from transacting. If the top of income distribution drives up prices when they trade in the housing market, the only option for curtailing prices is to prevent the trades.

That then leaves us with various public housing schemes to replace market provision, which, to my YIMBY ears, is catnip. Some of the most prominent YIMBYs in good standing are below-market-rate housing developers and baked into YIMBY assumptions about building a housing abundant future is a role for subsidized housing. How we go about that and what percentage needs to be covered via public provision is an open question, but it’s part of the pro-supply worldview.

Outro

Ok, climbing off my soap box.

At the end of the day, one Australian national’s opinions on the U.S. housing market don’t matter all that much, but engaging with ideas does. In articulating my thoughts, I’ve tried to understand what I think Dr. Murray is attempting to say. When I’ve done so in the past with fellow travelers more closely associated with Georgist strains of thought or working on these issues through a Strong Towns lens, I’ve learned something in the process. So that’s all to say, this type of exercise is less about debate and more about listening and introspection.

In that spirit, if I’ve misunderstood or misrepresented any of Dr. Murray’s positions, I fully invite him to take me to task in the comments or via whichever other medium he prefers. And, as almost an afterthought, I wish I would have heard more about his ideas on housing subsidy. He seemed to have some nuanced takes there that I suspect would have been thought provoking, whether or not they were persuasive.

Despite the seeming difference of opinion on theory, interpretation of fact, and preference with regard to policy, he seems like an affable guy. Should the opportunity present itself, I’ll publicly commit to buying him a beer — for the sake of the discourse.

And also, California’s property tax system incentivizes people to stay in place.

My father’s side of the family was from Amarillo, I spent many summers under the shadow of the Big Texan.

Obligatory lvt would fix that

Discretionary permitting = you abide by zoning, you still have to have some indeterminate number of public meetings to gain approval; the alternative is by-right or ministerial where, if you just follow the rules, you can go build what the rules allow you to build…sans the 18 public hearings.

Mayer, Christopher J., and C. Tsuriel Somerville. “Land use regulation and new construction.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 30.6 (2000): 2-3.

Thanks for engaging Jeff. A beer would be nice. Your photo is Hong Kong, no? I'll be there in Dec if you are! We can see if density there has made homes cheap ;-)

On the topic at hand, what's you view on why homes are built? Why are they not built? That's the key to all this.

Once we get past our areas of agreement, it seems to boil down to these questions.

I sense your answer is that property owners are in a hurry to build more homes (more per period, not just more density on a site) regardless of demand conditions. That as soon as redevelopment has a higher residual than the current use, property owners will rush to redevelop without regard to their effects of those actions on soaking up demand and hence changing future rents and prices. In this view, "supply" (rate of new housing produced in a period of time across a region) is tightly controlled by regulations, not by market choices of property owners about when to redevelop. But planning regulations don't control WHEN property owners choose to develop, only WHERE.

I disagree. And the economics on this is pretty clear, just widely ignored, as I explain here

https://www.fresheconomicthinking.com/p/explainer-markets-efficiently-delay?utm_source=publication-search

What is more interesting is when you look around the world and historically you find the property market doing the same old thing.

Your argument seems to revolve around wanting a different spatial distribution of dwellings. Fine. Planning DOES change the spatial distribution of homes, as intended. But make the spatial distribution more efficient will make average dwellings better and hence higher value.

Mike Fellman explains this in his Boyd institute interview.

Anyway, I have a book digging into the many details in this debate, so perhaps we should catch up after you've read that.

https://www.amazon.com.au/Great-Housing-Hijack-keeping-Australia/dp/176147085X/ref=mp_s_a_1_1?crid=3SE0YQSOAC9DD&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.KLD7-bxkI5wjl2TA5DgDyA.G2H1exl8zJbIqQhaguwScroB7jUXrXrzRF4GqTRbdHc&dib_tag=se&keywords=the+great+housing+hijack+by+cameron+murray&qid=1753139618&sprefix=great+housing+hijack,aps,307&sr=8-1

I work for large, international home builders. If we do not have clear permission, or as we would say in the states “entitlement“ to construct, then we cannot expect a rational investor to support a project without commensurate reward.

Capricious land use policy, and the ability for community groups to delay or cancel projects, increases the cost of building by increasing the price of investment, and by extending the investment horizon. There is a real cost to tying capital down for 10 years on what should be a five year project.

So, no surprise that large builders simply avoid regions that are Nimby by policy or proclivity.

As for government subsidized housing… You do know we have tried this before? The results were literally ugly.

It turns out that the government is really good at slowly building, dysfunctional, ugly, unpopular ineffective… Well, I seem to be running out of adjectives.

Anyway, the underlying difficulty is the US love affair with single-family housing. Even when the houses are built zero lot line, no lawn. We need a multi family product that appeals so strongly, that the average citizen is willing to put up with proximity to people. Nobody likes people.