Interview: Pablo Sepúlveda, founder and CEO at zlvas

Making zoning make sense

zlvas — pronounced zel-VUHs — is a startup making New York City’s ~4,000 page zoning code comprehensible.1 The team has built a platform that allows users to search, analyze, and export data about any given parcel in the city (as opposed to relying on an expert to interpret the city’s regulations like a priest parsing esoteric scripture).

The following is a conversation with zlvas founder and CEO, Pablo Sepúlveda, on the problems the team intends to solve, the product they’ve built to do it, and what they’ve learned along the way.

New York City Zoning — the opposite of simple

Jeff Fong: Alright, let’s start with a basic question. What is zlvas, what problem does it solve, and who does it solve it for?

Pablo Sepúlveda: zlvas is an urban analytics platform that simplifies access to zoning. Our goal is to make this information actionable, accessible and understandable. The zoning resolution is, like, 4000 pages plus and it's written in a very legalistic manner, so it's very hard to understand. It's dense, repetitive, and hard to interpret.

There's all these little tricks you could learn in zoning to really maximize the development potential of a property. It's the first interaction with clients [as an architect], so it's also the first opportunity to show off and get it right , “this scheme will provide maximum value”, right? When a client comes to you, they want to know really fast what they could build on that property. You have very little time, and it's high risk. You can make mistakes, which could lead to a lot of big litigation problems in the future. You got to make sure you get it right. So that's the broad reasoning.

JF: It sounds like your users, which may or may not be distinct from your customers, are architects working for developers who want to understand if they acquire a particular parcel, what they’re legally able to do with it. Is that fair?

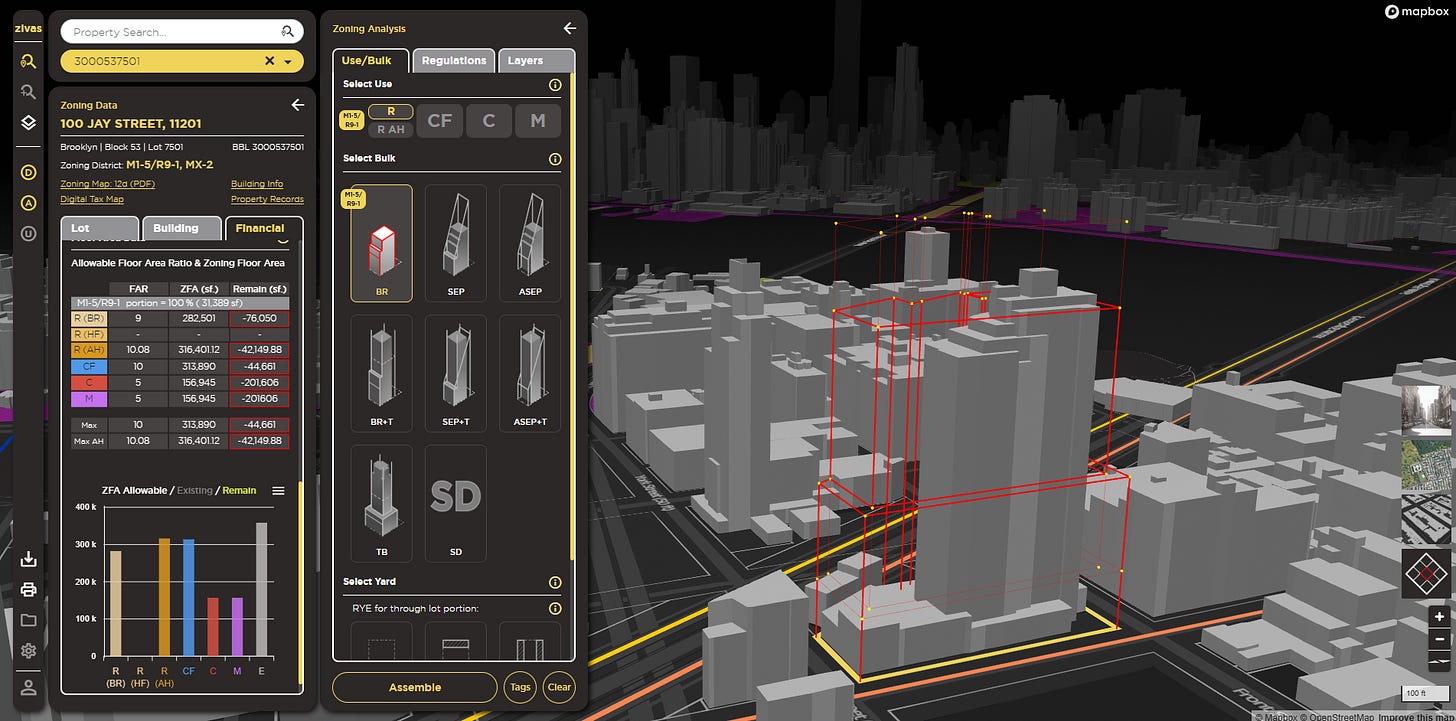

PS: Yes, the product outlines and visualizes the limitations and the opportunities of a property. It gives you instant access to the maximum constructibility, and a list of regulations that apply. And the way we're doing it, as an architect, is focusing on workflows.

But of course, there are many applications. At the end of the day, what a developer wants to know is the maximum constructibility and any potential limitations. With that knowledge, they can do their pro forma and determine viability. But then at the same time, we're trying to reduce the burden of research. Generally, a developer might have their own consultants in-house, or they might hire an architect to do this preliminary analysis, which could take anywhere from 8 to 36 hours. (Depending on the size of the property and the complexity of the districts). We're pre-processing that workflow. By digitizing the resolution, overlaying it onto maps, and making that information available with a few clicks.

JF: Follow-up question, it's not the case that there's just one answer to what you're allowed to build on a given parcel, right? There are trade-offs in terms of floor-to-area ratios, etc…like, there’s a massive list of parameters that, if you turn up the dial on one, you’re forced to turn down the dial somewhere else, right?

PS: Exactly. New York City is pretty interesting, zoning wise. It provides various paths for compliance as well as it reacts to the urban fabric. Depending on location and land use , there's different outcomes. For example, if you're within 100 feet of a wide street, you have more density. If you're at a corner, you don't need rear yards. So New York City zoning is very…reactionary is not the word…it's really susceptible to its urban surrounding.

It's not like other zonings where districts have a fixed set of rules. In NYC, if you're on a short dimension of the block, different rules apply than if you're on the long dimension of the block.2 So we're getting into the weeds by combining proprietary geospatial data with NYC’s 4,000 page zoning code to deliver instant site-specific insight.

The other thing is the flexibility that New York City allows. There's not just one bulk type allowed. You could do a tower, you could do a quality housing type bulk, (a term that has sunset with the latest amendments). You could do sky exposure plane buildings, and all that depends on districts as well as external factors.

JF: As you're describing the system as it exists, I'm imagining the grossest looking if else statement in a Python script that just goes on for miles. Is that kind of how it works? Are you able to actually look at the legalese and then represent that in a clear, deterministic way when you're trying to instantiate that in your tool?

PS: Exactly, and that’s why we've been only focused on New York City. We're really trying to make a platform that replicates that complexity and trying to simplify it so people can understand it.

If you just try to read this, this is the manner in which the text is written. So “10 feet of the wide street line shall be 100 feet beyond 15 feet of narrow street, street line, and 85 feet within 15 feet of narrow street, street line”. This is the level of complexity and interpretation required.

JF: I always knew that modern zoning was insanely complex, but I don't think I fully felt it until now. So, in the absence of a tool like zlvas, what? There's just some architect who has been around this stuff long enough that they're trusted to go and review what you just showed a minute ago, go back to the developer with what's possible, and then the developer works on their pro forma?

PS: Exactly. So that's the thing. If you want to be an architect in New York City, you really need to know zoning. It gives you power. It gives you a say at the table. You’re able to guide the client to give maximum value. But at the same time it's also frustrating. It’s [dealing with zoning code] repetitive. Early on I started creating my own Excel database of all the variables affected by zoning. For the past 10 years I reached a point where I said there has to be an easier way.There has to be a better way to do this because the system is inherently flawed.

As an architect, I worked on a project just South of midtown. We encountered an unexpected challenge: a neighbor complained we believed we had followed all the rules correctly. We had a zoning consultant on board and I personally reviewed the zoning regulations. However, we later discovered a misinterpretation that neither we nor the Department of Buildings caught.. The developer had to hire an attorney, resulting in costly legal fees. Every year there's millions of dollars wasted in legal fees for misinterpreting zoning. So the process in itself is inherently flawed, which is why we're really trying to simplify the knowledge.

JF: I'm curious now that you mentioned liability. In the situation that you just described, you had a zoning consultant and you as the architect in that situation both +1 the plan. You said that the city didn't see anything wrong on the application either. And then it sounds like a neighbor who may or may not be adequately described as a NIMBY got involved, and found something wrong that they were able to raise an issue with…at that point, who has liability? And was there something that was just clearly wrong, or was there an ambiguity in the code that you could argue was a matter of interpretation?

PS: In this case, the zoning requirements included a condition that was somewhat ambiguous and dependent on the context—specifically related to the required rear yard depth. The city did not identify any issues during the application review, but a neighbor later raised a concern based on a different interpretation of the code. Ultimately, it was a matter of interpretation rather than a clear-cut error. Situations like this are quite common given the complexity and occasional ambiguity of zoning regulations in New York City.

Making zoning make sense

JF: Amazing. I love the dueling experts.

So this sounds like a classic case of a founder starting a company to solve their own problems. You had mentioned putting together your own database in Excel. What does your data pipeline look like now? How do you get data into the tool and what does municipal data even look like? Is this a human expert, like you, looking at these zoning codes, trying to interpret what's available, and then just doing data entry?

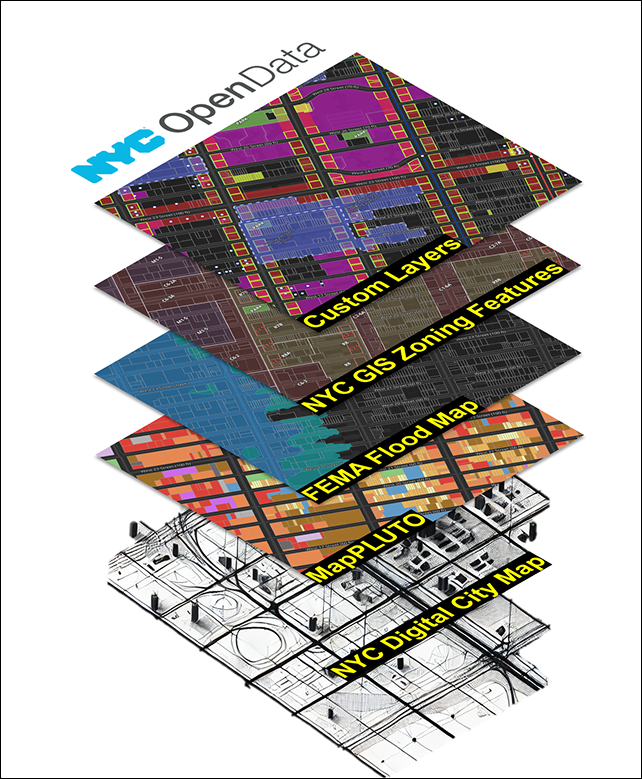

PS: Our raw material is open data. We rely on the New York Open Data Law that came out in 2012. It forces all parts of the government to release data to the public for free. We extract GIS information from different New York City municipal sources (planning, Department of Building, department transportation, etc). That's our raw material. Zoning is composed of text and maps. As a user of zoning, you start out by identifying the property and applicable district in the map, and then you go find that information in the text to understand the relevant limitations. So, our back-end is structured in that same way.

We start by processing map layers using advanced geospatial algorithms to subdivide each property according to zoning rules. These rules are then assigned to each georeferenced geometry, creating a comprehensive dataset that we upload to our platform for visualization.

JF: I'm starting to see what the data model must look like. I'm imagining each parcel as a unique object with a foreign key that connects it to all of the possible permutations of conditions, right?

PS: Correct.

JF: That's fascinating. And this might be a California question, but are there ever problems with interpretation? In the last couple of years, California has passed a lot of state-level interventions. We’ve seen things where a state density bonus interacts with a local density bonus and the result is disagreement on how to do the math on how much bonus the developer gets. Is that a problem that y'all run into with the interaction of state and local laws, or is New York more autarkic?

PS: New York City is unique in that sense. Nearly all rules including affordability requirements, density bonus, are codified into the text. In fact, they just recently amended the text. City of Yes passed at the end of last year. It’s the most comprehensive revision of the city’s zoning in, I don't know, 50 years. Because everything is so thoroughly integrated into the zoning resolution itself, the city tends to avoid some of the conflicts over state versus local rules that you see elsewhere.

Product strategy

JF: Let’s talk about plans. I get the basic idea is to make zoning legible. It sounds like that means specifically to architects and, more specifically, for architects who need to determine what's legally possible for a developer so that a developer can think about what's financially feasible.

Are there any plans in the future to directly connect the financial modeling piece into the existing product?

PS: Yes, we're exploring it. At zlvas, we use an analogy of a bottle and water to explain our approach. The bottle represents the maximum buildable envelope, these red lines that dictate the maximum envelope; you can't go beyond the bottle.The water is what you fill the bottle with. Different uses and design options within those limits. Right now, zlvas focuses on showing you the bottle and providing all the information related to the water, so you can make informed decisions.

In New York City, there are countless options and flexible regulations, like lot coverage, street wall location, dormers, that are challenging to digitize because there are so many possible variations. Our platform visualizes the bottle, highlights the relevant regulatory sections that describe the water, and links users back to the official text. In that sense, the financial modeling is more related to the water: Floor plates, building heights, number of floors. For now, we’re concentrating on demystifying the complexity of the regulations and giving users the detailed knowledge they need to do their own due diligence and cost analysis. Integrating direct financial modeling is definitely on the horizon as a natural next step.

JF: Got it. That makes sense. It could be really easy to boil the ocean then never solve the first problem.

PS: Exactly, yeah. We’ve considered modeling a building within these boundaries, which could eventually translate into pricing estimates. At this stage, though, we’ve accumulated a significant amount of valuable data. We’re actively exploring site selection, land value models and predictive rezoning, leveraging financial data such as tax assessments, market values, and land values, as well as comparisons with similar properties in the area. That’s the direction we’re most focused on right now.

JF: Yeah, that's super interesting. I know of a few other folks that are working on similar things. It seems like so much of this type of data is still just very analog or close to it. It always struck me as…not odd, but certainly frustrating, that there's not a series of APIs one could hit and just get the relevant data from a municipality about what can go where or even data on tax rolls and land values.

What’s next?

JF: So, you’re still in beta, when is the official launch?

PS: We're planning to launch by early August. Over the last couple of months, we focused on updating our platform to reflect the new regulations from the City of Yes. We've already been running trial versions to gather feedback. So far, we’ve had around 20 firms testing it, including developers, architects and urban planners. The feedback has been positive. People are excited about it. We originally built the platform to solve the specific challenges architects face, but we quickly realized that many of the same pain points exist across the industry. Real estate agents, developers, brokers, they all want to understand a property's potential, especially for listings or acquisitions.

JF: Got it, that makes a lot of sense. I can already hear the VC feedback of, “cool, but could you put an LLM on top?”, which is probably a yes, but also probably annoying.

PS: Yeah, and we’re actually working on that, and some of it is already live.

One of the most common feature requests from developers was a way to search for properties based on zoning criteria. So over the past few weeks, we implemented a natural language processing tool that lets users do exactly that. You can type something like “Give me 10 vacant lots of at least 7,000 sf, located within 100 feet of a wide street in an R6 district in Greenpoint, with annual property taxes under $500,000” and it returns a list of matching properties, which you can analyze or download as a CSV for further analysis. It’s already proving to be a powerful tool for early-stage site selection.

(the following is a short demo of the zlvas chat-based search function)

JF: That's super interesting. It makes sense that you go from “I have a property, what can I build on it” to “I know what I want to build, find me a property”. That seems like a more direct developer use case, even before they engage with an architect. So it sounds like this is going to be a SAS play, right?

PS: It's fundamentally a B2B SAS platform. We've also realized these past two years that the business model is just as much of a product as the technology itself .

Right now, we’re leaning toward a robust freemium model. We want users to access a meaningful amount of zoning and property data for free, because that aligns with our mission of democratizing information that’s traditionally been difficult to access. Then, more advanced features like the NLP search we just implemented, or the ability to download detailed 3D zoning envelopes, would sit behind a paywall, since they deliver immediate, time-saving value to professionals. That’s the structure we’re moving toward.

JF: That makes sense, and that's always a problem with any product. Pricing is always treated as an afterthought but it’s completely inseparable from product development itself.

Okay, just one or two more questions to round things out. What prompted you as an individual, to go from experiencing a problem to founding a company to solve it? What was that jumping off point for you?

PS: I’ve always felt the city should provide clearer, more accessible tools to help people navigate these complex rules. On one hand, the city sets important regulations you have to follow, but on the other hand, the way the information is presented can be really difficult to understand.

So, in early 2023, I started working on this idea with Felipe, a friend in Chile. Then I reached out to my brother Sebastian, who was finishing college and thinking about his next steps. We all saw the opportunity and decided to team up. Each of us brings different skills, and together we’ve been able to build a pretty exciting product so far.

JF: Anything else that you want folks to know?

PS: Zoning can feel pretty boring. What we’re trying to do is make zoning, not necessarily “cool”, but definitely more interactive and engaging. That’s our bottom line goal. I also feel like we have a civic duty here. Zoning impacts so much of our daily lives, yet most people don’t even realize it. There has to be a better way for cities to share this information. That’s where we come in, helping people truly engage with how their cities are planned and shaped.

JF: It's a beautiful sentiment. Well, I think that's all I got for you. Thanks for spending the time, Pablo.

There’s an emerging generation of startups — like zlvas and Hamlet — that have a fundamentally different relationship with government. In the 2010s, tech was all about supplanting, replacing, and disrupting. A decade on and those of us with eyes to see recognize the limits of that thinking. What we need, and what we’re starting to get, are technologists interested in making the necessary functions of government better and more legible to the governed.

Next week, we’ll take a step back and look at the challenges local governments face building, interpreting, and disseminating data. Some of these challenges are technical, some are organizational, many, though, may be conceptual. More on that next time as we round out our series.

The name is a reference to zlda (NYC’s zoning lot development agreement, pronounced “zelda”) and also selvas (Spanish for “jungles”, because NYC is a “concrete jungle”). As someone who also loves a good, extremely high-cost of entry deep-cut inside joke, game recognizes game.

For the non-architects, imagine a city block as a rectangle; the short dimension is just one of the two shorter sides of the block.

Great piece! This is very insightful.