Los Alamos Cost Disease

How Land Use Policy Blunts America’s Scientific Edge

Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) is one of seventeen national research centers under the purview of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Created in 1943, the laboratory is located in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and was the central site for the Manhattan Project. Today, the lab is responsible not only for ongoing nuclear weapons research, but also applied materials, energy, and climate science under the auspices of the DOE.

LANL has a problem, though: workforce housing. In this regard, LANL isn’t actually unique. Research centers across the country are all facing this same problem. The housing crisis is impeding the country’s ability to hire and retain the next generation of scientists. If you care about American science for reasons of national prosperity, security, or, really any reason at all, you ought to also care about housing.

How Zoning Strangles Science

Los Alamos is a dual city/county jurisdiction in New Mexico. It’s a community of roughly 20,000 people bordered by national park land as well as several tribal reservations. Despite a modest upzoning in 2022, the town remains dominated by a restrictive land use regime that maintains low-density development patterns and guarantees high housing costs.

The net result of all that is exactly what we’d expect. As housing has become more expensive, newer employees at the lab have begun to live farther and farther away. Approximately 66% of lab employees commute in from outside the county. The spillover from lab employees into neighboring communities like Santa Fe has created a knock-on displacement effect, pushing residents there even further out into Bernalillo County. And before anyone raises the “but maybe Santa Fe is just nicer” objection, a survey of 9,392 in-commuting LANL employees showed 75% would have preferred to live near the lab in Los Alamos County if they could.1 This has created a retention problem, which LANL leadership openly acknowledges.

At a 2022 town hall, Los Alamos National Laboratory Director Thom Mason explained (emphasis added):

Housing is listed in the exit interviews as kind of the number two factor in terms of our challenge; it’s really not so much hiring. ...We hired 2,077 people with great credentials and lots of enthusiasm, and exceeded our target for hiring. So our challenge is more on the retention…not so much getting people—it’s this increase in attrition in the early career staff after they’re here.

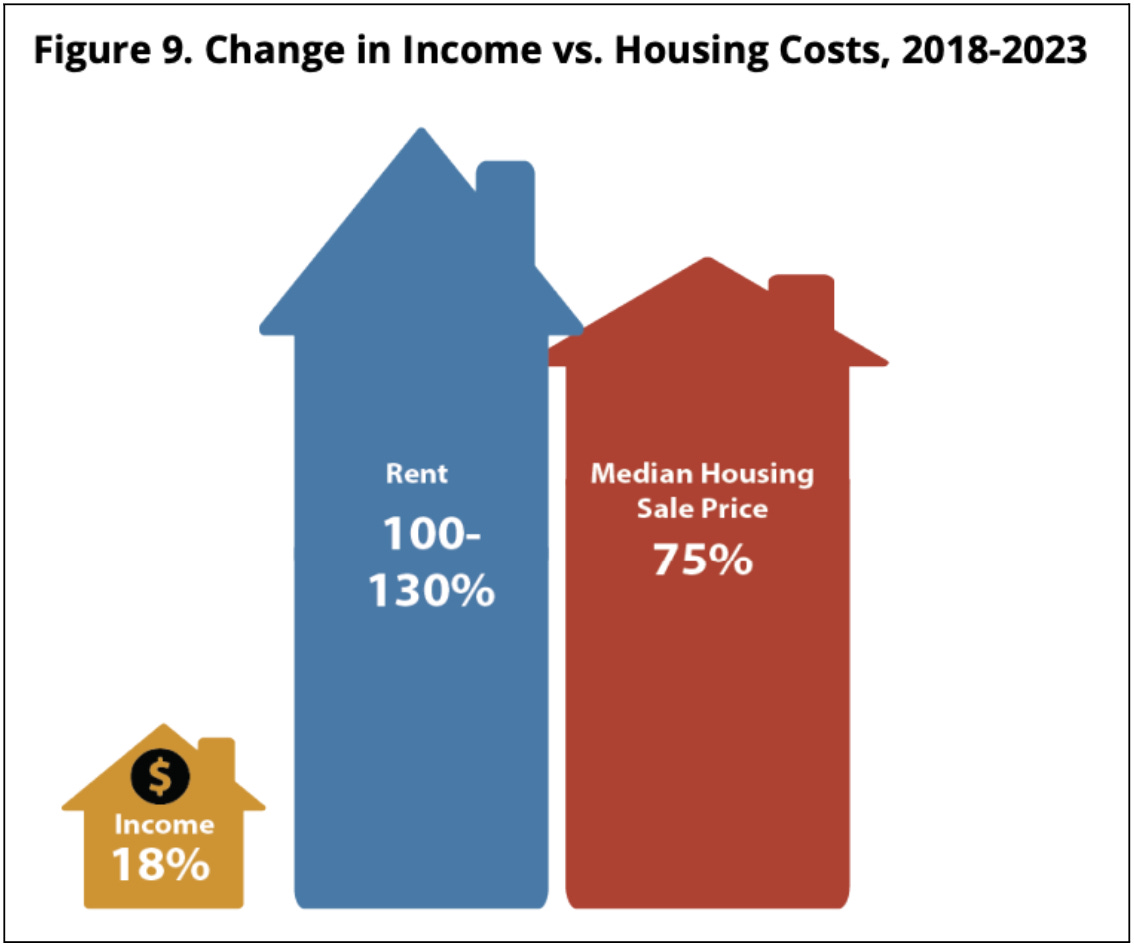

When we don’t build enough housing, prices outpace wage growth, subsequent waves of workers have to secure housing farther and farther away from economic centers, and less affluent communities already on the periphery get priced out even farther. It’s a tale as old as time (or at least 20th-century American land use).

Except it’s even worse.

LANL intends to hire 800-1,000 employees in 2026. This hiring will be enabled by additional funding via the much-discussed Big Beautiful Bill, and while it’s great that the lab came out of our recent budget conflagrations with a few extra bucks, there’s still a problem.2

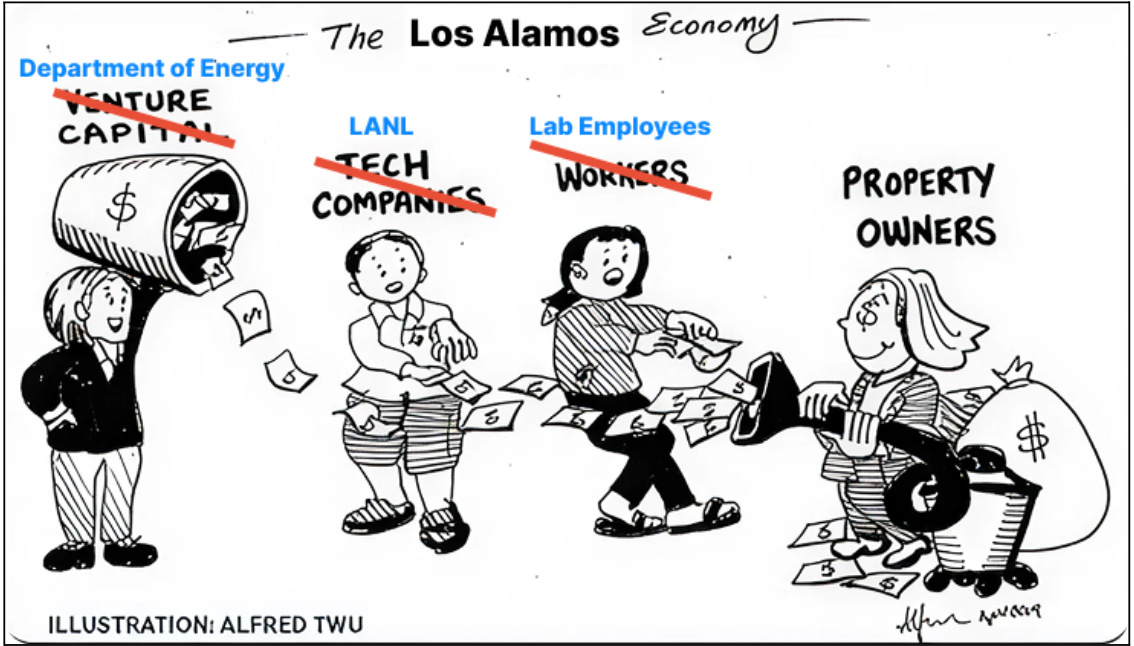

When the federal government pours money into LANL, that money covers payroll, and that payroll gets spent on housing, which pushes prices up. As long as supply remains inelastic, more money just means more problems (higher prices).

To clarify, some of those thousand hires will be backfills for retiring employees, not net new headcount. So maybe it’s slightly less bad than it sounds? Sadly, no.

The marginal retiring LANL employee doesn’t automatically free up a unit of housing upon retirement. Chances are they bought a home at the beginning of their career with the lab; so when they retire, they’ve paid off a $350k mortgage on a house now worth $600k. The replacement hire faces that $600k price tag on a starting salary. And herein lies an important part of the problem: every subsequent cohort of LANL employees has exerted a ratcheting effect on the region’s home prices. We can’t spend our way out of this problem.

Now, as bad as all that is, we still have room in our story for it to get even worse.

According to LANL’s Director of Community Partnerships, Kathy Keith, student interns, unable to secure any housing at all, sometimes camp in the nearby national forest. If our national science program depends on the interns not being eaten by bears, we need to admit we have a problem.3

Unfortunately, the situation in Los Alamos isn’t unique. Lawrence Livermore and Sandia National Laboratories face similar challenges in California’s expensive Bay Area housing market.4 And a host of other national science facilities are located in high-cost areas like Berkeley, Menlo Park, and the greater New York metropolitan area.

The problem isn’t restricted to government-funded laboratories, either. Consider Boston. The city is arguably the country’s biggest hub for pharma and biomedical research. It’s also notoriously one of the nation’s highest cost metro areas. At a private event I attended earlier this year, an investor gave a whole talk about how the city’s housing prices (driven by the city’s housing policies) were a major impediment to her firm’s ability to deploy capital against scientific research.5 Here again, housing costs are increasing the cost of scientific research for absolutely no added benefit.

What to do about it?

There’s a wide array of policy options to make sure cities with national labs are able to house the next generation of researchers shining the light of human knowledge into the gloom of our collective ignorance. The standard prescription includes allowing small-lot development/accessory dwelling units, abolition of parking requirements/height limits/onerous setbacks, and the adoption of by-right approval processes. There may still be financing and labor constraints to overcome in a market like Los Alamos, but, at least in housing, you have to legalize the market before you can go about creating it.

That said, my goal here isn’t to propose a model ordinance for Los Alamos or anywhere else. Instead, it’s to put a bug in the ear of all you science hawks.

Science doesn’t happen amongst people perfectly distributed across the American landmass. Even in this age of remote work and Zoom meetings, people still work together best when they can congregate as a community. Whether that’s in the same room, neighborhood, or city, the implications are the same. American land use that limits the number of people who can come together also financially impedes our ability to deploy capital in pursuit of scientific advancement.

If you’re worried about the pace of American innovation, if you’re anxious about our ability to deploy capital against problems of national import, you need to care about housing. Parochial concerns and status-quo bias will continue to bleed resources away from our national science efforts unless we address the housing shortage in the cities where science takes place.

p.s. If you work on science policy and are interested in learning more about the land use policy of it all, send me a DM. I know all the coolest kids already working on housing and am always happy to make an introduction.

The survey results appeared on slide 18 of this 2024 staff presentation to county council.

The BBB cut Department of Energy funding in aggregate, but increased funding for anything having to do with nuclear weapons, so Los Alamos Labs got a budget increase.

Sandia National Laboratory’s main campus is in Albuquerque, but they also operate a facility in California.

The event was under Chatham House Rule, so I’m not permitted to attribute.

As a Los Alamos resident obsessed about this issue enough to run for County Council twice, I can't tell you how good it feels to finally feel heard by somebody outside of the community. Everybody says the "standard prescription" is the starting point, but I'm giving up hope we'll ever get that far. Lots of nice concepts proposed and public money spent, but progress is painfully slow.

There's other challenges, as you said, but I don't think those with the power to change things really care about changing things, from staff to elected officials. They just don't have the skin in the game. I think we need a higher power to intervene, which is another reason why I'm glad somebody from the outside noticed.

If you haven't read it, there's a great book about how Los Alamos used to build workforce housing called Quads, Shoeboxes, and Sunken Living Rooms.

https://lahistorymuseumshop.square.site/product/quads-shoeboxes-and-sunken-living-rooms/9?cp=true&sa=false&sbp=false&q=false&category_id=7M3YJ5G7JCS7FX7VWNLFQWLH

This is great! I wrote a very similar piece more from a housing and industrial base perspective, but also highlighted LANL and the Navy's Danville Institute for Advanced Manufacturing. As a previous YIMBY organizer, its great to see more people working at the science and tech intersection as well!

https://industrialstrategy.substack.com/p/how-the-department-of-war-can-build