How Missing Middle Housing Cures NIMBYism

Normalizing change, growth, and duplexes

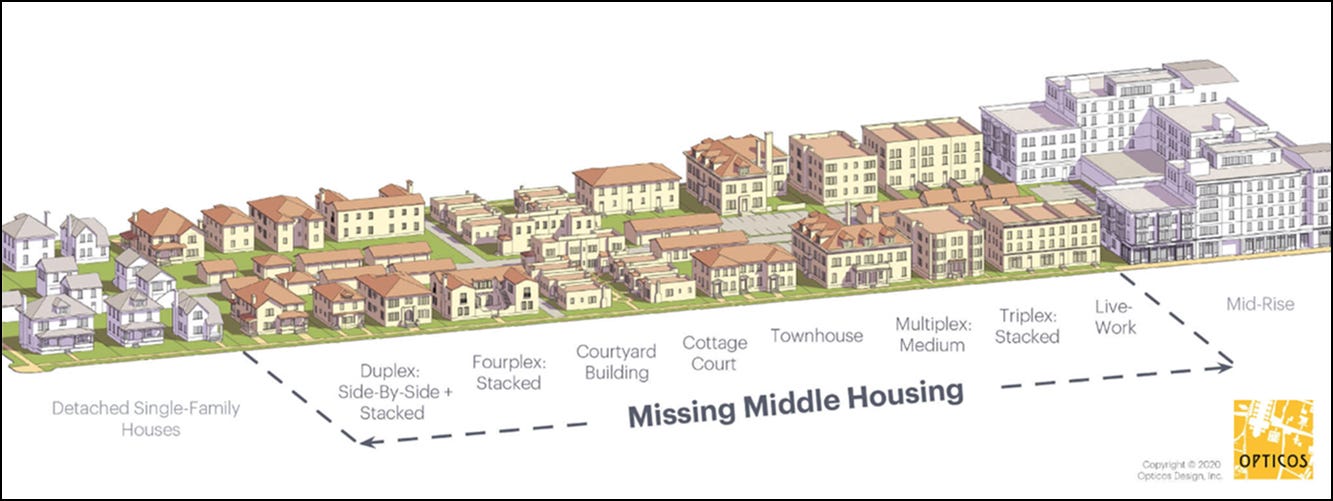

Most YIMBYs, if not most urbanists, are well acquainted with the concept of missing middle housing. These are all the types of housing — duplexes, triplexes, town homes, accessory dwelling units (ADUs), etc — that we’ve outlawed for decades and which would provide for “gentle” levels of density in the places we need housing most.

While the arguments for missing middle are usually couched in policy outcomes (more housing) and political expediency (maybe people will allow duplexes before they’ll accept apartment buildings), there’s an under recognized benefit to building missing middle. NIMBY homeowners are NIMBY homeowners because all they’ve ever known are neighborhoods cast in amber. The act of building missing middle housing, though, could renormalize an important idea in our communities: that it’s good and normal and perfectly ok for the places we live to change.

But before explaining how missing middle housing can help rewire the political economy of urban development, we’ll need to talk about how that political economy works today and how it generates the noxious obstructionism known as NIMBYism.

The Root of All NIMBY

Let’s start with what might turn out to be a controversial statement.1

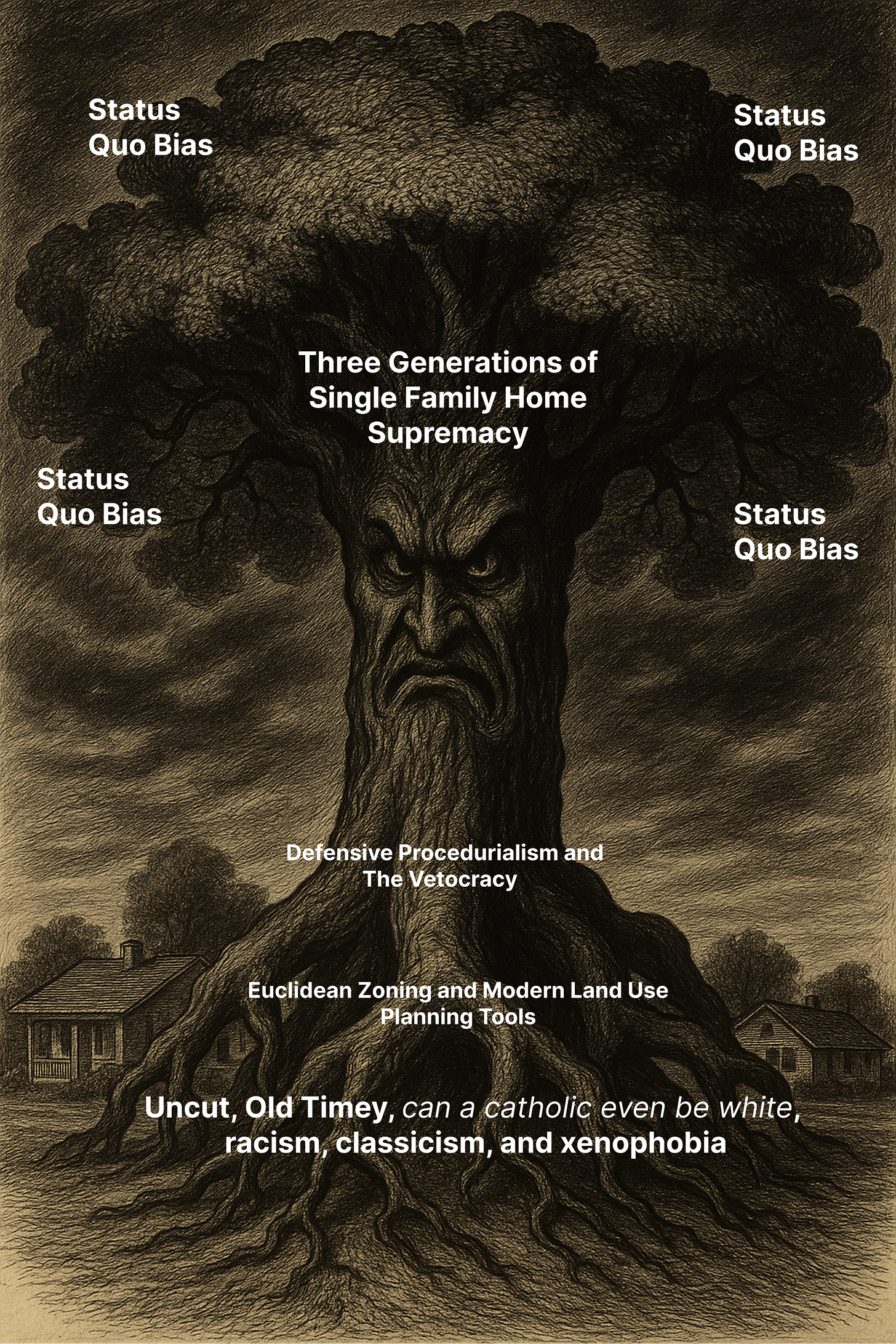

The proximal cause of NIMBYism in American communities is a small-c conservative aversion to change. It’s a status quo bias rooted in three generations of Americans believing that the way we build neighborhoods today is correct and good for no other reason than that’s all they’ve ever known.

Now, notice I said proximal cause. Obviously, American NIMBYism has deep roots in racism, classism, and xenophobia. Early proponents of zoning, what we use to separate uses, were explicitly using it to segregate people. After courts started telling cities they couldn’t enact ordinances that explicitly outlawed the presence of individuals on the basis of race or national origin, early nativist reactionaries (of which there were many) got creative. If taxing laundromats based on the number of carts used to deliver clean clothes (and levying the highest rates on establishments using zero carts) sounds oddly specific — it’s because it is.2

This arcane system of rules for micromanaging what can go where has its foundations in American nativism circa a century ago, but we have to also acknowledge the populist contributions in the second half of the last century.

In the decades after WWII, men like Robert Moses carried the torch of top-down technocratic managerialism. Moses and his ilk ripped up neighborhoods and put in highways connecting urban cores to increasingly far flung suburbs like so many overzealous children playing SimCity. His attempt to run a major thoroughfare through (perhaps over is a better preposition) Greenwich Village in New York prompted his now-famous fight with Jane Jacobs.

This episode and others like it is where we get the concept of community input and needing ten thousand public hearings before we let anyone do anything ever.

And, fwiw, the problem here isn’t so much that there should be a lot of friction when the government wants to eminent domain an entire neighborhood and put in a freeway; rather, the problem is that we applied the same set of brakes to someone wanting to build a duplex.

These are the historical ingredients that encoded NIMBYism into our institutions. So, make no mistake, American land use is rotten with our most illiberal impulses. And yet, even in these troubled times, I do not believe that most NIMBYs are literal eugenicists.3 Instead, I think there’s something else going on in (most) anti-housing hearts and minds.

Actually Existing NIMBYism

Thus far, we’ve established that institutional and individual NIMBYism can be different things, so let’s talk about the latter in more detail.

The common explanation for individual NIMBY behavior, that they’re all just defending their home values, is known as the Homevoter Hypothesis. The term was coined by political scientist William Fischel in his 2001 book, The Homevoter Hypothesis: How Home Values Influence Local Government Taxation, School Finance, and Land-Use, and represents the off-the-shelf explanation of NIMBY behavior.

In Fischel’s telling, homeowners act like risk averse investors. They seek to maximize the value of their home equity and all of their political behavior is reducible to rational economic calculation.

I believe this explanation is largely wrong.

If homeowners wanted to maximize the value of their property, they’d support the most liberalized land use possible that still prevented nearby noxious uses. In other words, as long as the apocryphal glue factory is kept out of the neighborhood, a parcel with a single-family home that already had regulatory approval for an apartment building is more valuable than one that does not. Moreover, agglomeration effects increase the value of land and restrictive land use constrains agglomeration effects. Big picture and long run, landowners would have more valuable land if they unshackled economic growth and let each other build.4

The problem here is that for a homeowner, their housing is two things at the same time: a consumer durable and a speculative asset.

Even if a homeowner accepted growth, they can’t spend imputed rent; owner-occupied housing is an illiquid asset.5 Up until the moment they cash out of their home, a homeowner’s house is a consumer durable. It’s a kitchen you cook in, a porch you sit on, a street you watch your kids cross. Because of that, homeowners aren't just maximizing returns. They’re balancing a discounted future payout against their consumptive enjoyment of their current environment.

When new development is proposed, it’s not evaluated the way an investor might value a stock or a rental property.6 Instead, homeowners ask themselves questions like: Will this change what I love about this place? Will it make my day-to-day a little worse, a little riskier, a little less familiar? Even if, objectively, liberalizing zoning would likely increase their net worth, the fear of disruption to their personal environment often outweighs the abstract promise of future returns.7

So, people like what they know and this drives a lot of our behavior.8 Perhaps the most illustrative examples here would be all the now iconic buildings that were absolutely despised when they were built.

The Eiffel Tower? Hated. The Golden Gate Bridge? Reviled. The Empire State Building? Ridiculed.

Obviously, these were all mega-projects that significantly changed the built environment, but the fundamental point remains: the gap between neighborhood character-murdering eyesore and beloved international emblem of a city’s essential spirit is a distance measured in time.

In a world where (a) homeowners have been socialized to feel that an unchanging built environment is normal and normatively good, (b) where prevailing political institutions make expressing those socialized preferences low cost (i.e. via the vetocracy), and (c) there’s no consumptive or financial upside from fighting the system…we get the world we live in.

However, when we change (b) and make it easy to build missing middle housing, we then change (c) giving people an incentive to defect. This ultimately begins altering (a) as people become acclimated to a different status quo.

If you’re skeptical that exposure therapy is the antidote to internalized NIMBYism, I’d like to offer you two thoughts:

First, we may just diverge on the degree to which we can change people’s opinions. Status quo bias is a hell of a drug, so maybe there are limits to how much we can move the hearts and minds of older homeowners who are already set in their ways. I personally think we can move this population — especially retirees — quite a long way, but I could concede that point and the argument would still stand.

You see, it’s not just about re-anchoring people who’ve already settled on the single-family housing status quo as correct. It’s also about enabling the next generation to grow up in a world where change is normal and growth is good. This part is less about altering anyone’s worldview as it is about normalizing change for the younger folks forming their opinions for the first time.

Societies can change much faster and more completely than individuals. Even if NIMBYism is too deeply entrenched in the souls of homeowners across America today, cohort replacement comes for us all. If we want to leave the kids with a better world, we’ll need to leave them better ideas as well.

Ultimately, this is not about convincing anyone to accept some specific type of built environment or particular level of density. It’s about re-acclimating our society to the idea that it’s good, normal, and healthy for the places we live to change over time. We need to embrace the idea that as the world changes, as our hopes and dreams and wants and needs shift over time, those changes become reflected in the built environment. The places we live need to be ongoing projects, not finished products.

Getting to that better place, though, will require us to accept that change is the only constant. In service of that, I believe the missing middle development can help us not only by providing more of the housing we so desperately need, but also by helping us regain our perspective.

At least to the other fifty terminally online housing nerds who’ll have strong opinions here.

In turn-of-the-century San Francisco, it was apparently common for laundromats to deliver clean clothes back to their customers. The tax, with its punitive rate for those who delivered customer clothing by hand, was a targeted attempt to drive Chinese establishments (which tended to not have delivery carts) out of the city. This was later struck down by the courts, prompting less on-the-nose measures for literally putting people in their places.

This is actually a hard rhetorical needle for me to thread. I’ve seen enough NIMBYs saying the quiet part out loud to know that some people oppose apartment buildings because they literally believe non-white, poor, or immigrant folk live in apartments and that these three categories of people are definitionally dangerous. But for every person I’ve heard express their lawful evil alignment out loud (or deploy thinly veiled language like “apartment dwellers” in ways that make me believe they mean the same thing), I’ve heard several more that I truly believe are hung up on more banal concerns like the inconceivability of reducing free unpriced street parking.

In fairness to Fischel, I’m condensing a 300-page book into two sentences. He does engage with the idea that homeowners aren’t simply profit-maximizing, but rather risk-averse investors more focused on preserving than increasing value. Still, I think this is wrong. Fischel offers a just-so, rational-choice story that renders homeowner behavior legible through economic incentives; but this flattens human motivation and gives us a reductive, one-dimensional account of human behavior.

An arguable exception would be if a homeowner took out debt against the value of their home. I’d still call a homeowner’s property illiquid in this scenario, though, as they’re borrowing against inaccessible value; i.e. the property is still not a revenue producing asset.

This is in juxtaposition to commercial real estate investors who view property as an abstracted stream of revenue, leading to an entirely different set of behaviors and outcomes.

There’s also the problem that most places — outside of California — have actual property taxes, so significant appreciation in property values can create unsustainable financial burdens on homeowners.

Ok, maybe not me especially; most of my small-c conservatism is concentrated in my love of ankle socks.