Stuck: The Story of Our Once and Future Urbanism

Restless, mobile, and perpetually moving toward good things

A normal book review tends to lay out the thesis, summarize the key points, offer commentary and feedback where the reviewer sees fit, and maybe close with a thumbs up or thumbs down. I’ve written those before but for what we’re talking about today — Stuck by Yoni Appelbaum — I'm going to do something a little different.

Instead of a comprehensive review, I want to zoom in on two parts of Yoni’s main thesis. Not only because they’re correct, but because they resonate so deeply with my own lived experience.

Urban mobility as the key to national prosperity

Stuck: How the Privileged and the Propertied Broke the Engine of American Opportunity does exactly what it says on the tin. Its main thesis is:

Americans exhibit a unique willingness to relocate from one place to another in search of opportunity–this mobility has been one of the key ingredients in both the country’s economic success as well as the breadth and depth of our civic institutions.

American mobility, however, has been on the decline for several generations–this has been driven by restrictive housing policies which make it materially difficult for people to move towards opportunity.

As mobility has declined, fewer people have been able to access opportunities localized in high-cost places like the Bay Area.

Further, as mobility has declined, our social institutions have atrophied as well, contributing to a general sense of social malaise and an epidemic of loneliness.

The basic economic argument isn’t a new one for me. Wearing my YIMBY hat, I see a big part of the work we do as making it easier for more people to move towards opportunity. What Stuck really drove home for me, though, was how exceptional American mobility actually is.

As it turns out, this topic came up for me the other week over dinner. Relevant to this conversation, the room skewed heavily Brazilian. I made the observation that even amongst the Brazilians I know who still live in Brazil, it’s not uncommon for folks to have visited — and often lived in — New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco…and not a single city (outside of their respective hometowns) in Brazil.

Though met with nods of agreement by everyone at the table, this anecdote underscores something unique—not about Brazilians, but about Americans: our cultural expectation that relocation is a means toward finding opportunity.1

Thinking about my own life, American hyper-mobility just seems normal.

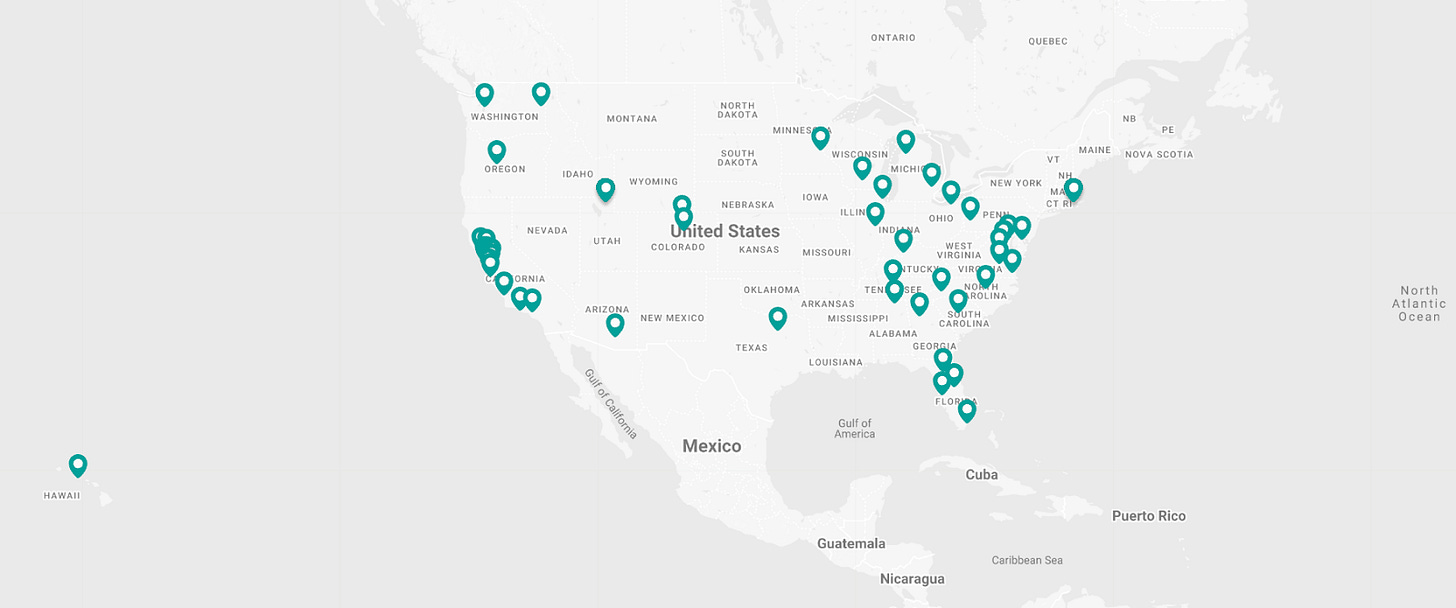

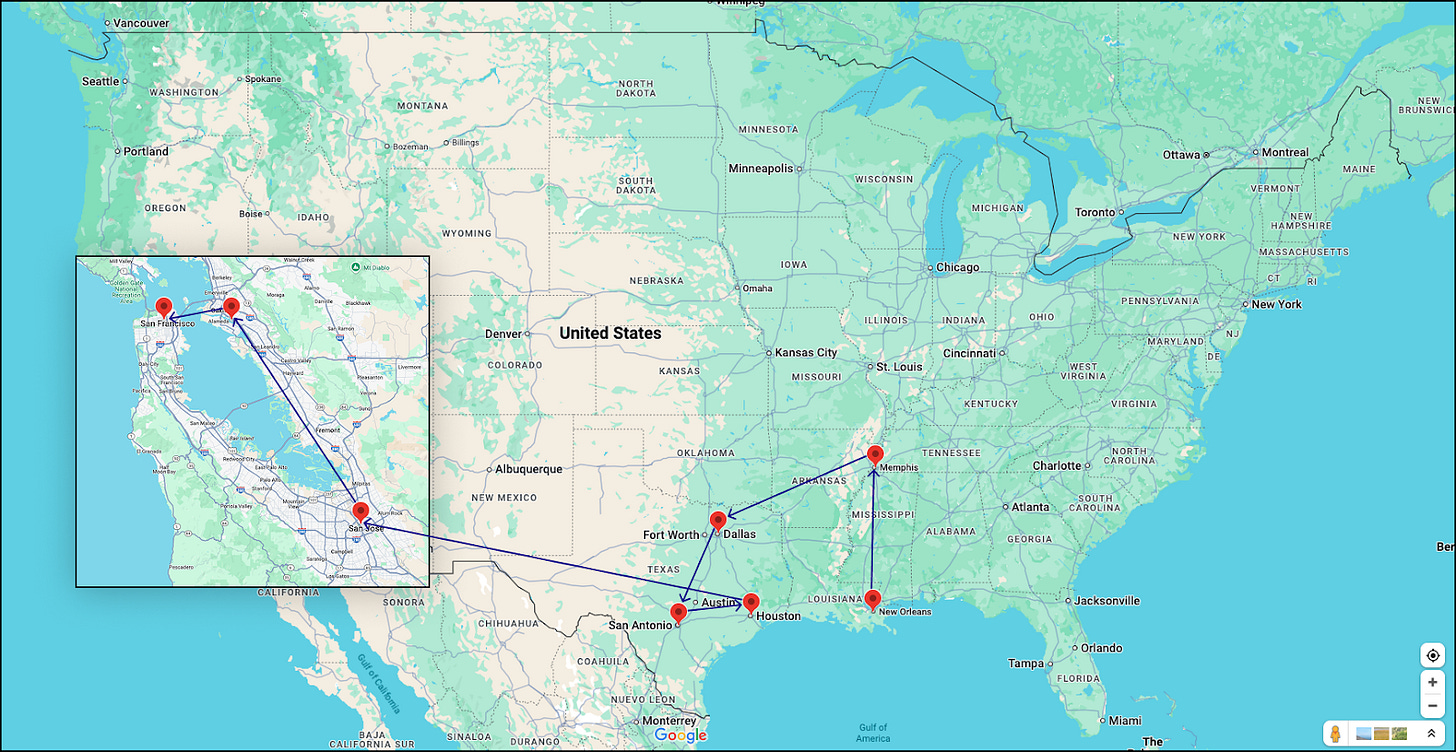

In the back half of my 30s, I’ve now lived in nine, going on ten, different cities. And each of those moves were moves towards something better. Going back to the book’s thesis, though, this is part of the American experiment that’s now broken. On the whole, we move a lot less. In the 19th century something like 1 in 3 Americans moved every year; in present day, that’s more like 1 in 13. And when we do move, we no longer move towards opportunity — we instead move away from cost.

Professionally, I made my bones in Bay Area tech between 2010 and 2020. During that period, there were plenty of credentialed strivers in the industry. But there were also lots of folks like me. I didn’t go to a fancy school.2 I didn’t even have a STEM degree. But labor markets were tight and that just increased everyone’s surface area to opportunity.

If I had to restart my career in 2025, holding everything else equal, I don’t believe there would be enough open doors for me to find one to walk through. Even back in 2015, if you weren’t in tech, it was hard to stay afloat in the Bay Area. Housing costs were insane, so unless you found a place at the top of the income distribution, you were SOL. There was no way to thrive as a barista or semi-employed artist filling in the gaps doing odd jobs.

Stuck doesn’t talk about it in these terms, but what the author’s describing sounds a lot like the way buying in at a poker table works. For the non-card-enthusiasts out there, when you play poker you’re typically obliged to commit a minimum amount just to sit down at the table. When I played in high school, this was something like $20. For high-stakes games in Monte Carlo or Macao, the buy-in could be more like $1 million.

What Stuck is pointing out is that we've effectively raised the buy-in to America’s most prosperous cities to levels few can afford. And if the only people that get to play are the kids who were trained to end up at McKinsey, Goldman, or [insert Big Law firm whose name I’m not genteel enough to know], we’ll be a more inequitable and all-around poorer society for it.

A Nation of Diasporas

So, on the economic policy / social mobility front, Stuck is a great addition to the Housing Theory of Everything discourse. But the book touches on another idea as well. Namely, that American mobility contributed to our civic institutions in ways that used to help us find and build community wherever we went.

I find this point fascinating for two reasons:

First, because it so completely accords with my personal experience.

Second, because it seems to be the part of the book that people resonate with the least.

YIMBY activism is a big part of my life. Something that comes along with that is existing within a larger community of like-minded activists across the U.S. (and increasingly beyond).3

A couple years ago, I had the opportunity to drop in on Seattle YIMBY’s monthly meeting. Given half the leadership got into housing activism in the Bay Area, we had more than a few friends in common.4 So, I had a great time making new friends and learning about local policy challenges. Currently, I’m on an extended stay in the greater Austin area and have been going to AURA (An Austin for Everyone) meetups. It’s been good to catch up with a different set of old friends and make a few new ones here as well.

The greater YIMBY-verse isn’t the only place I’ve had this kind of experience, though. In a part of my life that’s quite divorced from my housing politics, I have had the same experience hanging out at the local Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ) gym.

Briefly, because this is getting far afield from urbanism or technology, I grew up wrestling and doing Judo. As I’ve gotten longer in the tooth, I’ve retired into recreational BJJ as my sport of choice. For the uninitiated, the degree of difference between wrestling, Judo, and BJJ is roughly analogous to the degree of difference between tennis, badminton, and ping pong (and, by and large, we can describe these activities as being games wherein two people consensually attempt to non-consensually throw each other and/or bend each other's limbs the wrong way until someone gives up).

Returning to the Actual Point, I can show up in just about any city in the U.S. and find a BJJ gym willing to let me train for a day, week, or a couple months. What’s more, it’s not uncommon to end up meeting folks that trained with someone that you know in a completely different city. In fact, this exact thing happened during my first week training here in Austin; as soon as folks learned I was coming from the Bay Area, everyone who’d ever trained in NorCal started going down the “oh, do you know so-and-so?” list.

So, when Stuck talks about these lost civic institutions, the author’s talking about the kinds of diasporic communities that I enjoy being part of in my everyday life. I can go to most places in the U.S. and immediately find community in either a gym or YIMBY organization and that makes showing up somewhere new a lot more tenable than would otherwise be the case.

Implicit in this is that there was a positive externality enjoyed even by the people who didn’t move. If organizations like the Rotary Club or local trade associations proliferated, in part, because of folks moving to and fro, they still acted as sources of community and support for everyone who stayed in place.

The second part of this point though, is that although the U.S. worked this way in the past, it largely doesn’t work like this today. The book’s argument is something like:

Increased housing costs > reduced mobility > atrophied diasporic community organizations > epidemic of loneliness

One could take my personal experiences as counter to this part of the book's thesis, but I think they’re really the exceptions that prove the rule. I can’t come up with many analogues to my examples of YIMBY orgs and BJJ clubs. Moreover, when I’ve discussed the book with other people who’ve read it, this seems to be the part that they find least compelling; my takeaway from that is, perhaps, my direct experience with these types of supportive communities makes me better able to see their absence everywhere else.

Like I said at the top, this isn’t a book review in the strictest sense. There are things I could say about the depth of Stuck’s historical narrative, the accessibility of the writing style, or its place in a larger canon of recent works that includes the likes of Rothstein’s The Color of Law.

Suffice it to say, it’s a great read and I recommend it to anyone interested in American history, housing, or the central role of land use in basically every problem we face as a society today.

On a more personal note, Stuck resonated with me because it describes a version of the U.S. that I've experienced and from which I’ve benefitted. In this version, an American can chase opportunity from one end of the country to the other and know there’ll be some sort of community in every stop along the way. It’s this version, though, that’s increasingly difficult for other Americans to ever access.

Recognizing the unequivocally good parts of the country’s past seems like an important exercise, both for understanding where we are today and imagining where we might want to collectively go in the future. To that end, Stuck does its job well and Yoni Appelbaum has given me a whole new way to make every part of my life, somehow, about housing policy.

Postscript: For a more fulsome review, check out Ryan Puzycki’s write up on the book and its place in the current policy discourse. And for those curious — but unable to bring themselves to read a whole book — check out Yoni Appelbaum on the podcast Capitalisn’t for his argument in broad brushstrokes.

In reality, it was less nods and high decibel exclamations of tem razão; Brazilians don’t really do silent, understated gesturing.

i.e., I didn’t go to the type of school that someone who asks you, “So where’d you go to school?” would have ever heard of.

And if the word activist gives you the ick, feel free to substitute it for political entrepreneur.

Yes, that’s right. Everyone knows Bobak.

This is so interesting as someone probably 15 years younger; compared to my parents, who immigrated to the US in the 1990s when they were 18 and 22 respectively and moved nearly every three or four years until they had their first child, the culture of moving has changed completely for "Gen Z" -- even those of us who, due to immigration, don't necessarily have super deep cultural and emotional roots in one part of the US.

It's already unusual that I moved away from the area of my undergrad for work (almost all my college friends stayed in the Bay), and it's noticeably only a certain subset of young people who move often -- I went to a university that people do recognize, which is why I have access to opportunities that allow me to relocate easily on a "relocation/signing bonus". But in this cohort of affluent, well-educated young people with "good jobs" that are often finance-adjacent, I think we relocate significantly more than average. If my parents moved maybe every three or four years, I think in our 20s, we move closer to every two to three years. Like how serial divorcees bring up the average divorce rate.

Interesting theme about tradition of mobility fostering civic institutions to welcome newcomers. I haven’t read Stuck yet but I just read Uprooted by Grace Olmstead, who argues that we can continue to be mobile to chase things but ultimately we need to learn to be “Stickers” wherever we decide to stay since that gives the truest sense of satisfaction and makes for healthier communities. I think there’s a certain aspect of seasonality and life phases that go with this (sometimes we want to be boomers and other times stickers) And we should have buildings and institutions like coliving and coworking and zoning flexibility for popups, and good public spaces that encourage and cultivate this in our towns and cities.