The Biggest Challenge Facing Robots? Surviving Us.

Robots need social skills

Robots are about to be everywhere. Waymo is on the verge of rolling out in Seattle and Denver with plans to scale vehicle production via a new factory in Phoenix, Arizona. Serve Robotics now delivers food in Los Angeles, Atlanta, Dallas, and Miami. Whill’s automated wheelchairs ferry folks around the Alaska Terminal in SeaTAC. Earlier this year in Austin, I even witnessed a PUDU BellBot running takeout orders from the kitchen to the front-of-house. The robots are already here and in a few short years they’ll be ubiquitous.

Their jobs, though, won’t just require them to navigate the physical world. They’ll also have to learn to navigate a social environment populated by unpredictable human beings — and, increasingly, each other.

Product Design Means Dealing with People

Autonomous systems must navigate a world of unpredictable humans doing unpredictable human things. A child chasing a ball across the street or a human driving erratically all introduce uncertainty into the environment.1 Worse still, sometimes these environmental hazards (us, we’re the hazards) try to directly interact with an autonomous system.

At a fundamental level, these robots — Waymo, Serve, Whill, PUDU, and whatever other example we can find — all do the same thing. They navigate to a pickup, collect a payload, and transport that payload to a drop-off. Although that’s no small feat from an engineering perspective, it’s a fairly straightforward set of product requirements. Where our product reqs get more complicated is where we introduce people into the mix.

This complication stems from the fact that, famously, humans can be assholes.

Exhibit A: an incident from last year in San Francisco. Two absolute walnuts stood in front of a woman’s Waymo, preventing the vehicle (and the woman) from driving away. Why did they see fit to hold her hostage, you ask? She wouldn’t give them her phone number.

The Waymo being a Waymo, there was no pissed-off driver to lean on the horn or correct either young man’s behavior with a gentle bumper tap. Of course, this isn’t the first time someone’s taken advantage of Waymo’s do-no-harm programming. Earlier this year in Los Angeles, a few of the vehicles got torched during the protests. More recently, there’s also this guy engaging in hand-to-mirror combat with a Waymo (while it waffles between trying to drive away and trying to not run over the guy’s feet).

The common denominator among each of these situations is that with an autonomous vehicle, there’s no driver to run you over or step out of the car with a baseball bat.

While those examples are Waymo-specific, there’s a deeper psychological element that applies to all automated systems. For most standard-issue human beings, it’s psychologically easier to throw a brick through a window than it is to punch another human in the face. We simply don’t come out of the box ready to hurt each other.2

So what’s an autonomous vehicle operator to do?

Cuteness as a Defense Mechanism

Well, one approach is to make the robots more human. The best example of this approach is this humble delivery unit built by Serve.3

If you notice the design, the “eyes” are most definitely meant to look like eyes. The whole is honestly kinda cute and if you squint you might see a resemblance to a character from a certain litigious mega corporation’s IP.4

Deterrence effects aside, the exterior design is meant to help the units navigate social terrain even beyond being too cute to kill. The company’s delivery robots have an entire gestural language meant to communicate intent with people in all the subtle ways we already do in real life. This approach was designed to handle those semi-scripted situations that humans navigate every day in the public sphere, like figuring out who gets to go at a four-way stop where everyone showed up at basically the same time.

In fact, the company’s design language is such a big part of the product, Serve founder Ali Kashani has an entire presentation on the concept.

Now, these exact design features don’t necessarily port over 1:1 for self-driving cars (or wheelchairs or food runners), but the general considerations remain the same. Autonomous systems have to interact with people and that will probably entail some degree of anthropomorphization as well as product features designed to hook into the sometimes subtle way humans navigate each other in public spaces.

But what about deterrence?

When I talk to folks about the kind of deterrence features we discussed earlier in the piece, I often get the following question in response: “Why not just let the robots defend themselves?” In these conversations, that usually amounts to a Waymo to lean on the horn to move a pedestrian along. More aggressive interlocutors have even suggested features like mace.

Arming even semi-autonomous units is a categorically bad idea. Once you build and deploy an automated weapons platform, whether or not it’s less-than-lethal, it will get used. Moreover, distancing people from violence makes it easier for them to commit violence. Like I said at the top, we have to train a person to be psychologically able to hit someone over the head with a truncheon; programming the abstract variables that may at some point cause a robot to harm a human being is a much, much lower bar.

Suffice it to say, killer robots are bad and I’ll eventually deliver a couple thousand words on the topic. But not today.

Planning for Robot-on-Robot Violence

Beyond interacting with humans, robots will also have to learn to interact with each other. For an early look at what some of these challenges might look like, we have an amusing example of robot on robot violence in Los Angeles.

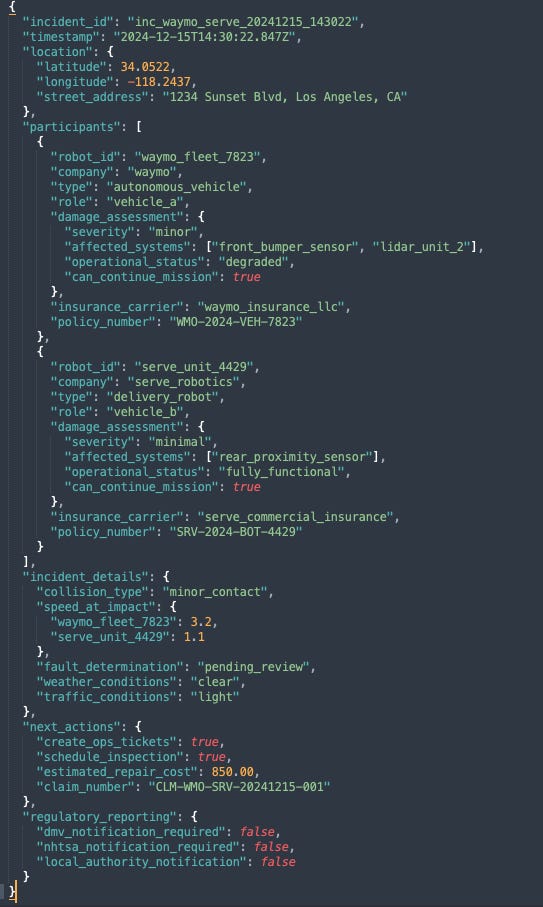

As you can see in the video, the Serve Delivery unit is crossing the street when the Waymo makes the right turn on red. The Waymo bumper taps the Serve and both go into “I just hit/was hit by something” failure mode. After a moment, the Serve continues crossing the street, clearing the way for the Waymo to continue on its route.

Note that in this scenario, neither robot is able to “talk” to the other. The interaction is the emergent result of both systems handling the situation as they’ve been designed. That worked out in this case, but it could have just as easily resulted in both units freezing in place, unable to move if their designers had planned for collision scenarios with different assumptions. In a world more densely populated by autonomous systems (where these types of unplanned interactions become much more common), I suspect we’ll see standardized protocols to enable inter-system communication.

Picture another Waymo<>Serve fender bender. I could imagine unit-to-unit communication that lets each robot know what they’re interacting with, triggers specific behaviors, and maybe even creates a ticket for the companies’ respective ops teams to check the units for damage and issue a claim based on some preexisting agreement.

As always, necessity is the mother of invention. So, when/if/how these types of systems get implemented, it’ll be to solve particular problems (like if you 100x the number of Waymos and Serves and this results in them constantly running into each other). There is a scenario, though, where regulators enforce standardized communication protocols (so they can track, disable, or requisition data from specific units) that creates a sort of autonomous robot HTTP in the process.

Outro

How any of this plays out is beyond my ability to predict in detail. I don’t presume to think I can second guess what the teams working on these systems will actually dream up in the coming years. What is clear to me, though, is the class of problems that these teams will be working to solve.

As autonomous systems become good enough at their core functions to commercialize, integrating them into everyday life with actual humans — and, increasingly, each other — will raise a whole other set of design challenges that will have to be addressed to build products that work and businesses that scale.

There may also be issues with moral hazard. For a through treatment, see Andrew Miller’s Robotaxis Have a Bullying Problem.

This is well established in genocide studies. One of the precursors to genocide is the dehumanization of the target population, often likening them to rodents or other invasive or disease carrying pests. Famously, part of the impetus for the Nazi death camps was the fact German soldiers tasked with murdering folks at gunpoint quickly began experiencing mental breakdowns.

Disclosure-ish: Serve Robotics was started as a special division of Postmates where I used to work. Though I don’t have any financial interest in the company, I bear personal fondness for some of the humans who still work there to this day.

You really thought I was gonna say it out loud, didn’t you?