The Tubbs Proposal

And he wants the government to make money off it, too

Last week, I read an op-ed from Michael Tubbs, one of the candidates running for California Lieutenant Governor. On grounds of substantive policy, I’m picking up what he’s putting down. There’s a bigger picture commentary, though, and it’s about reimagining the political economy of development in California. The Tubbs Proposal offers a way for the state to rethink its relationship with development and move towards a more sustainable way of funding public goods.

A Lieutenant Governorship for Housing

Tubbs is the former Mayor of Stockton and during his tenure he established a reputation for experimentation, piloting a universal basic income program. He’s also taken a pro-housing abundance stance while still maintaining working relationships with equity and tenant’s rights groups that, at least in California, have historically been skeptical of the mainline YIMBY position. So that’s his general vibe, but the job Tubbs is running for, the Lieutenant Governorship of California, warrants some explanation as well.

In California, the Lieutenant Governor’s (Lt.) race is an independent election, completely separate from the main gubernatorial race. It’s its own role and more than once California has had a governor with an Lt. less than fully to their liking.

So, what does the California Lt. actually do? Traditionally, not that much.

The position has little in the way of formal authority and, if the Lt. doesn’t have a good relationship with the Governor, can turn into a bit of a do nothing post. Tubbs, however, is painting a more ambitious vision for the role.

In his op-ed, he points out that the California Lt. sits on the boards of the California State University (CSU) and University of California (UC) — the state’s two public university systems which both happen to be major owners of public lands. Based on this, his proposal for how he’d spend his time in office is twofold: (a) develop housing on these public lands as part of the larger effort to address the state’s housing shortage and (b) use that development to generate revenue to funnel back into California’s higher education systems. Tubbs writes:

We can solve multiple problems at once if we’re willing to think differently about public assets. My plan is simple: make public land work for the public purpose.

Across the UC and CSU systems, that means long-term (from 50-99 years) ground leases that keep land in public ownership while unlocking it for housing. Mission-aligned developers would build mixed-income homes for faculty, staff, students, and surrounding communities, helping stabilize the very people who make our universities thrive.

The land stays public. The housing gets built. And lease revenue flows back into what matters most: financial aid, scholarships, and campus infrastructure. All of this strengthens our higher education system without raising tuition or selling off public assets.

Suffice it to say the YIMBY corner of my soul loves this proposal. If any place in the country needs more housing, it’s California. The other half of Tubbs’ proposal, though, is worth appreciating in detail as well.

There’s Still Gold in California’s Hills

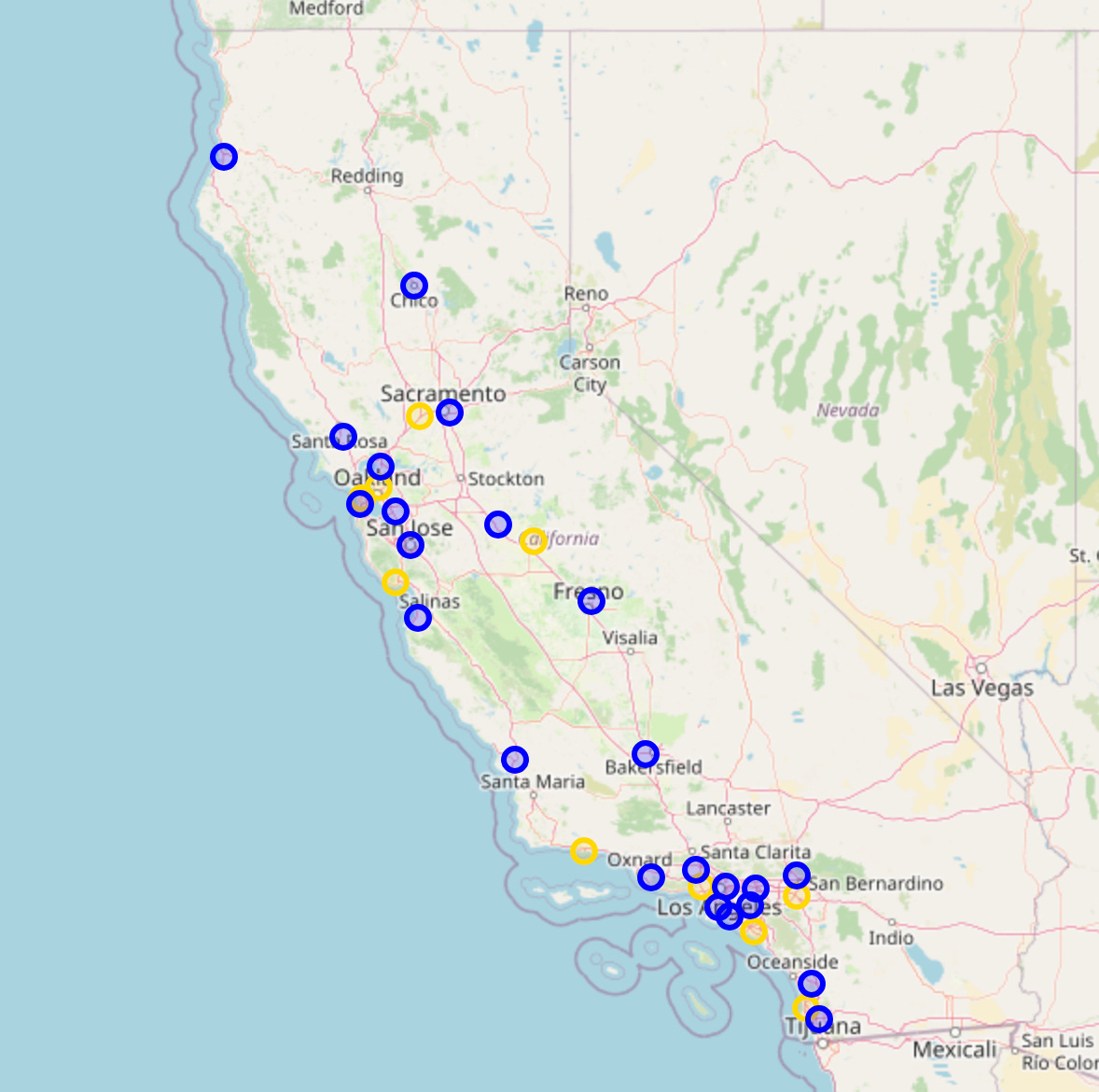

The famous statistic the Governors of California love to repeat is that if the state were its own country, it would have the 4th largest economy in the world. California’s economy, though, isn’t uniformly spread across the state; it’s concentrated in the three major economic centers of San Diego, Los Angeles, and the San Francisco Bay Area.

Where the economy booms, land becomes super valuable. And land in California generally, and its three major economic hubs specifically, is worth more than any old-timey prospector could have ever imagined. The problem with California is that most of this value remains in private hands. Where other states1 recoup appreciating land values — values created by economic growth and public infrastructure — via property taxes, California (mostly) does not.

In 1978, voters in the Bear Republic approved the aptly numbered Prop 13 which dramatically curtailed the government’s ability to collect property taxes. Fast forward to today and the state’s median effective tax rate for homeowners is something like .7% (for reference, Illinois is more than double that at 1.83%). Because of the way Prop 13 works though, the spread on this is quite wide with documented instances of specific properties being taxed at effective rates of .06% (yes, we just moved out an entire ten’s place).2

So, a lot of California’s wealth is locked away in the earth and Prop 13 prevents the state from monetizing much of it through taxation. However, taxing private land is only one way to get at all that value; per the Tubbs plan, the other is leasing out land held in the public trust. The UC and CSU systems own a lot of dirt, and I could not be more supportive of the idea that those holdings ought to be put to good use in support of public education.

My bigger hope, though, is that this proposal heralds a new, and badly needed, paradigm for local development. One that reorients us towards growth and sets up cities across the country to thrive in uncertain times.3

Public Assets for Public Profit

There’s a common refrain amongst local officials that housing does not pay for itself. The idea is that new housing allows new people to move into your community and new people require services. From a fiscal perspective, the thinking goes, it’s better to permit hotels and retail that offer ready-to-tax commercial activity (and don’t involve as much getting yelled at by local NIMBYs).

But land leasing gives us a way around that problem.4 When a municipality (or whatever specific organ of government) simply situates itself as the landlord in perpetuity, we can act with certainty that the public purse will capture the upside from development.

A great example of this is from the opposite end of the country in Falls Church, Virginia. In 2017, the town decided to rebuild the local high school. The city had two options: (a) increase everyone’s property taxes by $1,050 or option (b) use 10.3 acres of publicly owned land for redevelopment, monetize through land leasing, and only raise everyone’s property taxes by about $280. After a voter education campaign and a series of public hearings, the council moved forward with option B. Families got a new school, the community got a high-density mixed use development, and the land defrayed most of the cost.

Land leasing provides a way to ensure (and demonstrate that) development pays for itself. When governments then channel the proceeds back into specific public goods, we’ll be able to break through some amount of reflexive NIMBYism and give YIMBY advocates easier shots on goal.

There’s one other angle here, as well. It may be controversial (and I want to stress that this is my thinking and not necessarily my read of how Tubbs sees the world). It’s the idea that the government can and should be in the business of making money.

Hear me out.

Cities own a lot of assets in the form of real estate. For a long time, it’s been the norm to sell off public lands for a one-time windfall and then assume that any appreciation in property values will get partially recouped through property taxes. The problem with that is, on a long enough timeline, you get things like California’s tax revolt.

Instead, cities could be active participants in their own development. Developing and retaining ownership of public land could create non tax streams of revenue in perpetuity. In reality, this isn’t an especially off the wall idea. In a bygone era, New York City worked like this.5 Dag Detter and Stefan Fölster’s 2017 book The Public Wealth of Cities also made a similar call for better deployment of public assets (and provided recommendations on how to stand up a professional wealth management apparatus to do it).

Critically, the point is not that everything municipal government does should be on the basis of profit; instead, it’s a call for cities to embrace the idea that making money is good and that profitable public ventures can help pay for the things that communities need to make their cities great.

Outro

Whether we’re going to see progress on any of this soon remains to be seen. Mr. Tubbs has an election to win and a traditionally ceremonial office to turn into a vehicle for institutional reform. I have my hopes, but the practical politics of it all are in hands which are blessedly more capable than mine.

That said, I’m excited to hear these ideas out in the mainstream. When a candidate, even one as earnest as I understand Michael Tubbs to be, campaigns on a set of ideas, it’s because they think those ideas could be political winners. And that gives me hope for where California may be going next.

Prop 13 caps at 1% of assessed value at the time of purchase. For tax purposes, reassessment only occurs if the property changes ownership. This means that if you bought a house in San Francisco in 1978, you’re basically paying 1% on the inflation-adjusted value of what the property was worth when Jimmy Carter was President. The definition of “ownership” also does a lot of work here. Savvy property owners put properties under the ownership of transferable trusts. When an owner wants to sell a property, they just transfer control of the trust. This way, the ownership of the property never changes — it’s still under the trust — so reassessment never occurs.

This requires doing a little math. Based on figures in the SFChron article, one long-time owner pays around $1,100 annually on an assessed value of $94,000 (≈0.06% of a ~$1.7M market value), versus a new buyer paying around $44,000 on a $3.7M assessment (~1.2%).

Read: the absence of a functional federal government; or, worse, the presence of an actively hostile one.

This may or may not be technically true in different places, but when/where enough people believe it enough to influence official attitudes, it’s a problem all the same.

Daniel Wortel-London’s The Menace of Prosperity documents this shift in “fiscal imagination” amongst early NYC policymakers.

What are the politics of Prop 13 repeal? It seems disingenuous for progressives and liberals to give conservatives of the 70s all the blame for the existence of Prop 13 when there is no blue wave in CA pressing for repeal. Granted, the politics are not symmetrical, but I think Ds in CA deserve to own a piece of this.