Urbanism-as-a-Service

The New Cities Part III: Solving problems people actually have

This is part 3 of 5 in Urban Proxima’s series on the theory and practice of building new cities.

Part 1: That Time Google Tried to Build a Neighborhood

Part 2: Outsourcing Sovereignty

Part 3: Urbanism-as-a-Service

Part 4: Urban Larping

Bonus: Dreaming of Atlantis

Welcome back, y’all.

In last week’s installment, we discussed Paul Romer’s Charter City idea and how that morphed into Startup Cities like Próspera in Honduras. This week, we’re discussing two examples of a different type of city building project — California Forever and Ciudad Morazán.

Both of these projects are building instead of reforming. Like I’ve said before, the past hangs heavy around our necks. If sclerotic political systems, car-centric transportation networks, or change-averse incumbent residents are difficult to overcome, perhaps there are benefits to starting from scratch.

California Forever, and ever, and ever

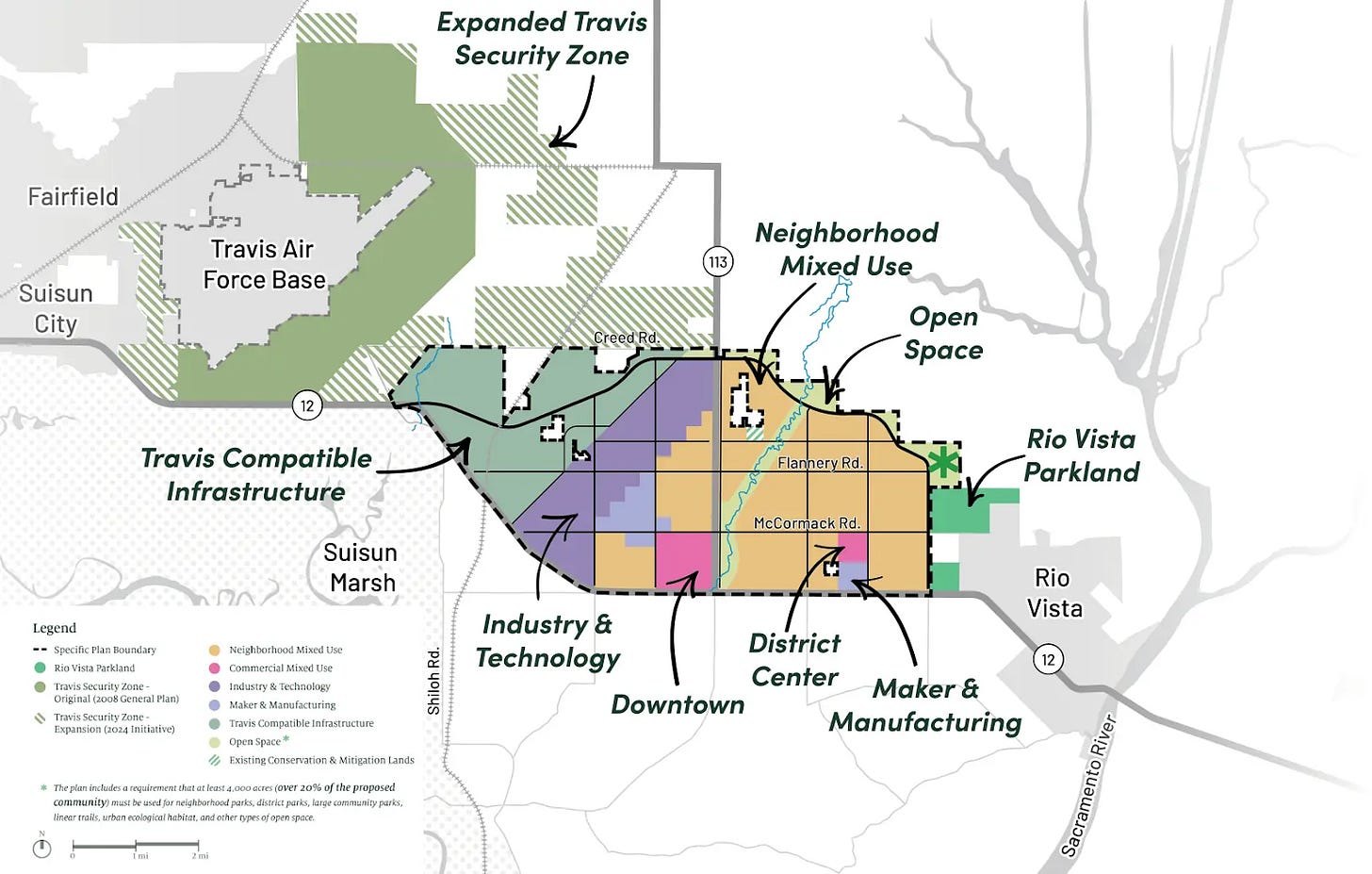

California Forever started out as a plan to develop over 55,000 acres of farmland (approximately two San Franciscos) in Solano County, California. The area sits northeast of San Francisco, south of Sacramento, and the parcels in question are all in unincorporated Solano County (i.e. in the county, but outside any currently existing cities).

California Forever is emphatically not trying to build a bedroom community or suburban sprawl. The team behind the project envisions a fully fledged city, complete with its own local labor market. They also want to build an environment where walking, biking, and transit are at least as convenient as driving.

In pursuit of both those ends, the current plan lays out only four designations for zoning:

→ The Neighborhood Mixed Use zone (orange) is a place for homes, schools, parks, small businesses, and local shopping streets.

→ Downtown and the smaller District Center (pink) are places for major offices, cultural institutions, major shopping, entertainment, and larger apartment buildings.

→Maker & Manufacturing (light purple) is a mixed-use zone modeled on the warehouse district you see in many older cities – an eclectic mix of jobs, nightlife, lofts, and small-scale manufacturing – kind of like R Street in Sacramento.

→Industry & Technology (dark purple) is a place for manufacturing jobs, industry, warehouses, major hospitals, and other large uses. Residential uses are not permitted here.

Notice that there's no single-family zoning; i.e. there’s no place where the only thing that's allowed is single-family detached housing. That doesn’t mean there won’t be single-family style housing, it’s just that where there’s housing, there’ll be a diversity of types.1 On top of that, residential areas will be mixed-use by default. Wherever there’s housing, there’ll also be dentists, cafes, public schools, and the like.

Baking in these two design choices — density and mixed use zoning — will help address many of the challenges North American cities struggle with today.

Consider transportation.

Anyone who's had the misfortune of driving around Los Angeles or Houston knows that personal vehicle use stops working at a certain scale. Mass transit, however, doesn’t just automatically pick up where cars leave off. Transit needs density at a certain level to work really well, and there’s an awkward intermediary phase where a city is dense enough to make driving inconvenient, but not quite dense enough for transit to be effective.

Now, Yimbyism is gradually bending the long arc of history towards densification in existing cities. In the meantime, though, this is exactly the type of problem that a project like California Forever gets to sidestep by building a transit friendly environment from day one.

Another reason California Forever is noteworthy is its approach to building an economic base.

As we’ve discussed before, cities develop around some foundational economic activity; they don’t spring up randomly for no reason. California Forever plans to handle this economic question in two ways.

First, by setting up between San Francisco and Sacramento, it’s filling in an underdeveloped area between two of California's major economic hubs. Over 80,000 people do the Sacramento-to-San Francisco commute, so it’s not unreasonable to think that California Forever will benefit from proximity to either city’s employer base.

That said, California Forever doesn’t want to be another bedroom community (even a walkable, transit-oriented one). The intention is to bring in employers and even there I think they benefit from location.

Building a new town between two of the largest economic centers of gravity in one of the most productive regions in the U.S. will make it easier to attract businesses than if they were to do the same thing in, say, the middle of Oklahoma. Even at the regional level, real estate still boils down to location.

When and how the project moves forward is TBD. Solano County has an ordinance prohibiting residential development without voter approval, so there’s a bit of politicking to do. After a couple false starts, the California Forever team has established a friendlier relationship with the powers-that-be and are hopefully on the path to winning over the county’s voters.2

Pivoting to a different project, entrepreneurs in Honduras are also trying to build a better city. But whereas California has long suffered from a political aversion to new housing and car-centric urban design choices, the folks behind Ciudad Morazán are tackling a different set of problems particular to Honduras.

Return to Honduras

Ciudad Morazán is a development located just outside the Honduran city of Choloma in the country’s northwest. It’s currently home to about 200 people, though it’s designed to eventually host a population of 10,000. Like Próspera from part II, it’s a semi-autonomous jurisdiction incorporated under the country’s ZEDE program.

At this stage, its physical footprint is relatively small and, from an urban design perspective, the built environment seems fairly nondescript. That said, neither its current scale nor its architecture are why we’re talking about it today.

There are three things worth understanding about Ciudad Morazán: (a) the problems it’s solving, (b) who it’s solving them for, and (c) how the business model makes the whole thing pencil out.

The paramount objective of the community is to free its residents from fear. Fear of going out after dark and being assaulted. Fear to leave the kids to roam around alone on bicycles because someone may run over them or take them in a gang. Fear of opening a small business because of extortion. Fear of hurricanes or earthquakes that could destroy savings of a lifetime or lives themselves.

Honduras, even by regional standards, is a dangerous place. Violent crime threatens not just people’s physical safety, but also their ability to get ahead. It’s hard to build wealth under constant threat of robbery or extortion, so a big part of what Ciudad Morazán is selling is basic safety.

The development staffs its own private security and is surrounded by a literal wall. And while gated communities in the U.S. make me all kinds of itchy, Ciudad Morazán isn’t selling separation from the hoi polloi to rich people. The community’s residents are all middle-class Hondurans.

The community’s typical resident works in a nearby factory or call center and pays the equivalent of $141 USD a month in rent to live there. And this gets at the business model underlying the whole thing (and why this was set up as a ZEDE in the first place).

Residents don’t own any of the real estate in Ciudad Morazán. The city qua legal entity retains title to everything and leases out both residential and commercial space. The entire business model is based on this lease revenue and residents pay almost nothing else in terms of taxes or fees.3

Now, there’s a few things going on here.

On a policy level, Ciudad Morazán is operating an economically efficient “tax” model. They’re internalizing land rents and rolling the proceeds back into public investment (in actual English, they’re cutting out all the future landlords that might be able to pocket exorbitant rents by dint of having bought the right patch of dirt at the right time and channelling all that value back into the community).

This system also incentivizes Ciudad Morazán to entrepreneurially invest in public infrastructure. Good public investments promote growth and increase demand to live in the city, thereby increasing the value of future leases.4 Put in other terms, the business model is all about farming agglomeration effects.

As it stands, the project’s future is unclear. The low tax, lease-based model was only possible because of the flexibility provided by the ZEDE program. The current administration in Honduras, however, wants the development zones declared unconstitutional and dissolved. Próspera is currently suing the Honduran government in international court and although Ciudad Morazán isn’t a party to that suit, its future probably depends on the outcome there.5 So, just like California Forever, Ciudad Morazán hasn’t completely sidestepped the reality of navigating politics.

Platform Urbanism

Both California Forever and Ciudad Morazán want to build environments that allow people to say “yes” to each and every one of the following questions:

→ Are there good jobs here?

→ Am I safe from violent crime?

→ Can I walk my kid to school?

→ Can I bike to work without fear of getting hit by a car?

→ Are there housing options for me now and in future stages of my life?

And, most importantly:

→ Can I get all of that at a price I’m actually able to afford?

In both cases, they’re setting out to solve the practical challenges of urban life and, in the process, build better places for people to live.

They’re not focused on creating regulatory arbitrage opportunities for transnational capital.6 Neither are they creating cities as monuments to authoritarian megalomania. They’re also not imagining their projects as scaled up intentional communities.

What they are doing is more akin to building platforms.

To borrow a quote (and, tbh, an entire concept) from zach.dev:

Platforms are enablers. The classic example is Facebook. Facebook (at least in its early days) said, “here’s a bunch of tools to easily share your life with friends and family. Do as you please!” Customers liked it. The platform enabled wildly diverse behaviors: arguing politics, humblebrags, flirting, digitally stalking your ex, asking for advice, and wishing Grandma happy birthday.

Zach continues:

The platform analogy suits the city. Real cities are more like the chaos of a Facebook feed than a typical SaaS app. Cities give their customers enabling tools: physical and social technologies like roads, sidewalks, rules, and police. People then do as they please. There’s not a “right way” to use a city.

City building (or reforming, for that matter) should be all about creating the best possible places for people to live their lives. That means solving the problems that get in the way of people figuring out what “best” means for them.

Cities, properly understood, are never-ending group projects. So when we talk about city building, we’re really talking building the setting in which that group project takes place. The stage isn’t the play and the soil isn’t the tree, but, in either case, the latter requires the former to exist.

Creating the necessary substrate for urban life is exactly the tack that both California Forever and Ciudad Morazán are taking. And it’s how we should understand the process of building new cities.

Yes, And

California Forever and Ciudad Morazán give me hope that we can try new things, even in the context of city building. They also reinforce my belief in the necessity of entrepreneurs.

To be clear, this is not about valorizing startup founders or for-profit companies. In my view, an entrepreneur is anyone who recognizes an unmet need and finds a way to organize resources and navigate constraints to solve a problem. Sometimes that’s in the context of business, but it could just as easily be in politics or any other part of life. Looking at the projects we’ve discussed today, I see that spirit in both of them and I’m all the happier for it.

Do I still believe in reforming existing cities? Absolutely (I was once designated a deep Yimby by someone with the authority to grant such titles). But I also believe that we should be throwing all of the spaghetti against the wall, hoping that even half of it sticks. As urbanists seeking to build a better world with more (and better) cities in it, we need to be in our yes, and era.

Next week we’ll continue our discussion on city building with a post I almost decided not to write.

For folks already familiar with Praxis, I want to commit to taking it more seriously than it deserves…before dropping the steel man and explaining what I really think. That said, I never want to be in the habit of dunking just to dunk. I see a real harm in all the oxygen things like Praxis consume and that’s what I hope to highlight next week.

In the meantime, thanks for reading. Leave a tip if you’d like to support my pack-a-day pontificating on the internet habit, though feedback in the comments (positive or otherwise) is the true mana which sustains my work.

You can see proposed floor plans, including those for single-family detached homes, on this page (scroll down a bit).

There’s a whole backstory on the politics here that includes the corporate entity behind California Forever trying to buy up land anonymously, freaking out federal authorities (because they thought it was CCP), and the resultant backlash when investigative reporters from the NYT identified who it was that acquired the land. All of that’s beside the point I’m here to make, but happy to regale folks if anyone asks.

Ciudad Morazán does assess a 7% income tax, but only because the Honduran government wouldn’t allow them to go all the way to 0% when the ZEDE was created.

For my Georgist folk out there, the answer is yes. The founder behind Ciudad Morazán is totally a Georgist (but in the Spencerian mold).

Honduras is party to the Dominican Republic – Central America – United States Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR). This treaty establishes certain rules for trade that include when/how a national government can expropriate the property of foreign investors. Próspera’s argument is that the current Honduran government can’t renege on the 50 year ZEDE agreement it signed with a previous administration. For its part, the sitting Honduran government sees the entire ZEDE program as an intolerable violation of its sovereignty that should have never been recognized in the first place.

We could discuss if or when that type of thing is actually good; but, either way, that’s just not the raison d'être of either project.

I think one of the biggest arguments in favor of a charter city like California Forever / East Solano ties back to your last post. It’s surprising how little variation and experimentation there is among municipal codes and institutions. Not sure how it came to be this way, but city staff and elected officials tend to have a very intense herd mentality, frequently stated as a desire to conform to how other cities do things, which is stronger than their desire to solve local problems.

Creating places that can just *try* different policies and demonstrate they are safe is a valuable public service.