A Missive on Subsidiarity

In Response to Addison Del Mastro

Last week, Addison Del Mastro published some thoughts on Zoning and Subsidiarity. He framed it as a thinking-out-loud piece, closing with a call for comments. Since this topic happens to be one of my weirder niche interests, my "comment" ended up becoming a whole post.

So, if you enjoy thoughts about thoughts (particularly on the architecture of political institutions and their impact on policy), you’re in the right place.1

Because he’s a rigorous thinker and excellent writer, Addison starts by defining his terms. So we’re all on the same page, I’ll echo him here:

Wikipedia has a good simple definition: “Subsidiarity is a principle of social organization that holds that social and political issues should be dealt with at the most immediate or local level that is consistent with their resolution.”

Subsidiarity is often taken to mean localism, and it is often used in the context of advocating for the devolution or decentralization of political or economic power. However, as both of those definitions imply, there are cases where the level of authority consistent with the resolution of a problem is going to be above the local level.

As a guiding principle, subsidiarity shows up all over the place. Addison points out that the Catholic church ascribes to it in ordering the church hierarchy. It’s also the guiding principle in the division of responsibilities between Brussels and member states in the EU. It also shows up in discussions about American Federalism and even in some of the more esoteric conversations on competitive governance (in which I have sometimes taken part).

When I’ve considered the topic in the past, I’ve grappled with how to determine what things need to be planned at what scale. Directly referencing our definition, the operative question becomes “How do we determine the level of government best suited to solving a given problem?”.

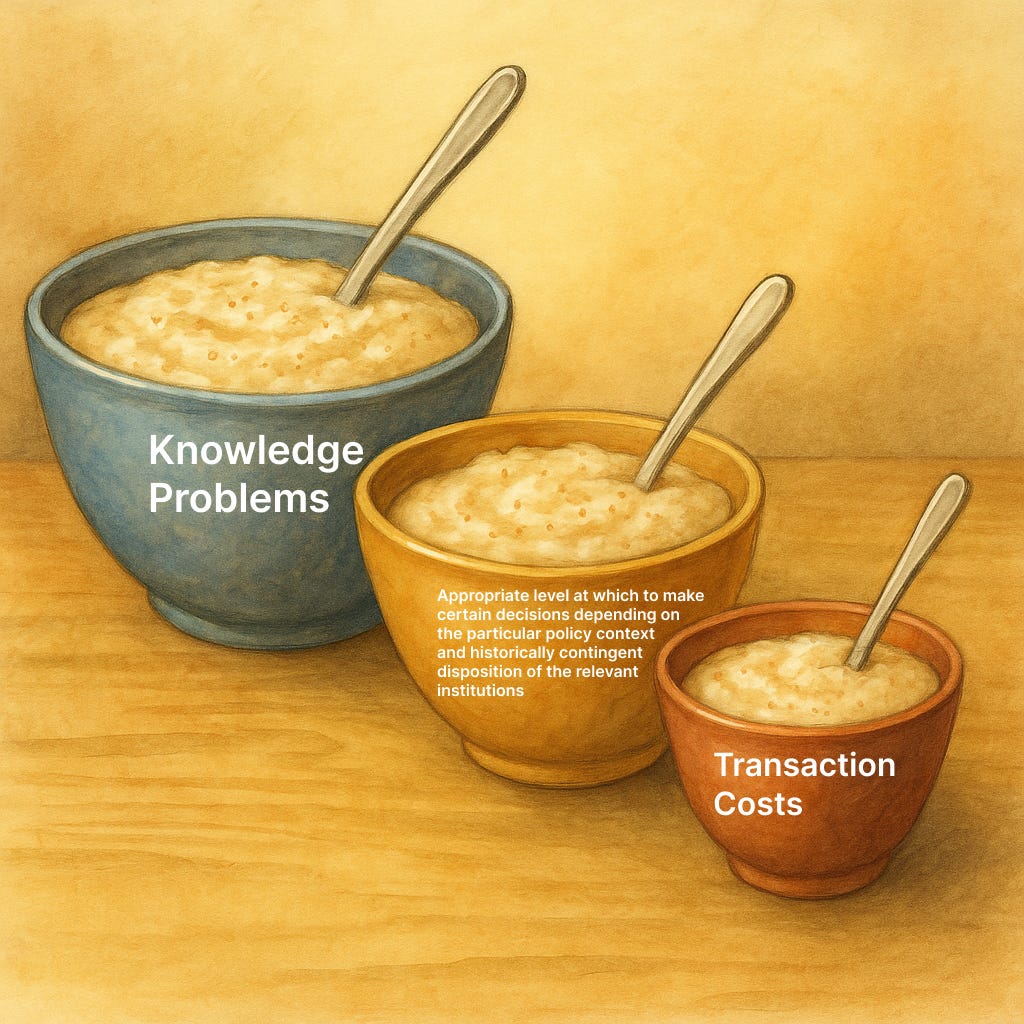

Continuing to be self-indulgently abstract for just a little longer, one way to answer is that we need to pick the level at which we can maximize local knowledge without succumbing to transaction costs.

For example, the federal government can’t possibly know the right minimum lot size to ensure areas where people use septic tanks don’t devolve into literal cesspools, so we leave that problem to county and local governments.2

Similarly, there are certain things that simply can’t (or at least really, really shouldn’t be) planned and provided for piecemeal. Transportation systems, road grids, and sewage systems are difficult for decentralized private actors to provide. Examples like Gurgaon in India show what happens when decentralization goes too far: transaction costs are overwhelming, coordination problems emerge, and we get poorly functioning infrastructure as a result.

Ok, that was a lot of theory, let’s make it more practical.

Talking about local governments having full autonomy on questions of land use, Addison writes:

The problem is that housing is a regional issue. What local zoning powers do is sever housing from the rest of the regional economy. So that’s one way in which it’s inappropriate for land use powers to reside with localities.

He goes on to also call out that another problem is:

…the fact that local politicians represent a small number of people, and local elections can be swayed by a very small number of local players. Vesting power over a regional issue in such a small number of people is not exactly democratic. Nor is the fact that almost by definition, this process offers no representation to the people who would live in a locality if the housing were more abundant and more affordable. That representation—would-be residents of [X County/Town/City] who are currently priced out or who were pushed out—is hard to capture, but those people, at least in the aggregate, become more apparent when you think about housing (and job markets, and commuting patterns) regionally.

To which I respond…YES, A HUNDRED TIMES YES.

However, Addison then goes on to say:

NIMBYism is what happens when a regional power is devolved to a hyperlocal level. It’s a mismatch.

To which I respond…kinda. (warning: this is about to get pedantic)

My reformulation of the statement would be: NIMBYism is what happens when a regional power is devolved to a hyperlocal level given our existing political economy.

There’s an alternate timeline in which a butterfly flapped its wings three seconds earlier and the Georgist movement of the late 1800s actually won. In this world, cities would have begun to fund themselves through land rents, creating municipalities oriented toward positive-sum growth.3

Instead, we got institutions built to segregate people by race as well as class and designed to extract wealth from some and redistribute it to others. And this is a point I always feel is worth belaboring: most of the bugs in our current system exist because, for the people who originally built them, they were features.4

So, it’s not exactly accurate to say devolution of land use authority to city governments is the problem. I’d say, instead, that devolution of land use authority to city governments running governmental operating systems that were purposefully structured to extract rent and externalize costs is the issue.

All that said, none of that changes what we need to do. Addison is unequivocally correct that state authorities need to override housing resistant local governments.5 Ultimately, I suppose I’m just quibbling over why I think he’s correct. But what else is the internet for if not spiritually starting a post with actually and then belting out a thousand words.6

That’s it for today. Let me know in the comments if any of that made any sense. And thanks to Addison for writing a post that succeeded in causing me to spend an entire Sunday afternoon behind a keyboard.

Extra Credit

And if you’re more into the personal anecdotes or scathing criticisms of crypto bros and petro state autocrats, no worries — more of those kinds of stories are in the queue.

This is one of the few legitimate use cases for minimum lot size regulations.

Believe it or not, Georgism was a capital b Big Deal once upon a time. As to why the movement petered out politically, well, that’s at least a thousand word post on it’s own.

I realize there’s some popular fatigue with tying public policy issues back to race, so I want to be clear that I don’t introduce that line of argumentation looking for cheap rhetorical points. The history of land use regulations — why they were invented and what they were used for — is so profoundly racist, classist, and xenophobic it beggars belief (ok, at least for some of us). This is throughly attested by books like Rothstein’s The Color of Law and even parts of Yoni Appelbaum’s Stuck; however bad you might think the story is, if you haven’t read these two books, it’s worse.

Although, to be comprehensive here, passing state laws is just step one in actually changing policy. Spoiler: local governments love ignoring state mandates.

Don’t answer that.