Senáḵw High-Rise

First Nations urbanism in Metro Vancouver

The Squamish Nation in Canada recently broke ground on a major mixed-use development in Vancouver. It’s an example of not only pro-housing development in a supposedly “built out” metro, but also an example of how a government’s revenue model influences its decision making (and eventually shapes the built environment itself).

It’s a fascinating story with lessons for how we ought to think about modern urbanism; it’s also amazingly under-reported for how interesting it is (a problem which I hope we can start addressing here today).

Once upon a time, Europeans showed up in North America. Murder and mayhem ensued and native populations across the continent ended up on the business end of colonialism. This frequently involved the expulsion of native populations from their lands, one example being the eviction of the Squamish from the area known as Senáḵw (pronounced sen-AH-qw).

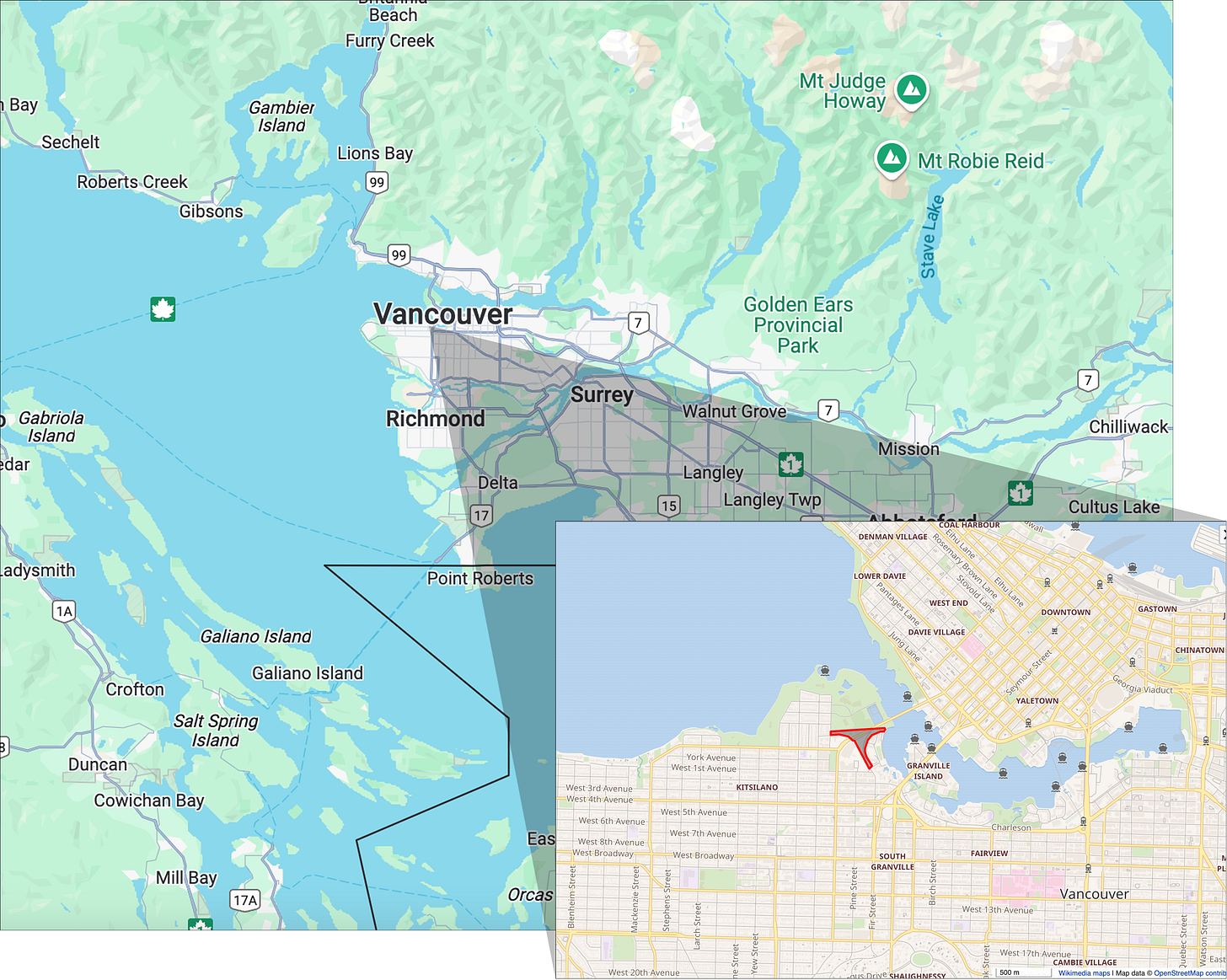

Senáḵw — literal translation, the place inside the head of False Creek — is an area near present-day downtown Vancouver. It was originally settled by the Squamish and, in 1887, formally declared Kitsilano Reserve n.6.1

In 1913, the government of British Columbia removed the Squamish residents from the area in what has since been deemed a dick move. This was also technically illegal even under Canadian law of the time.2

In 1977, representatives of the Squamish Nation launched a court case against the Canadian government. After a 26-year legal process, the Federal court of Canada awarded the Squamish 10.48 acres (of the original 80 acres of reserve land) — in the middle of Metro Vancouver. Fast forward to 2019 and the members of the Squamish Nation voted to develop the land; after securing partners for financing and development in 2022, they broke ground and started building.

The Project

Once completed, the development will include 6,000 market-rate apartments, 1,200 below-market-rate apartments, and over 100,000 sqft of commercial space — all built surrounding a major transit hub.

If you’ve worked in real estate (or perhaps are just better at spatial reasoning than I am), you may have already realized this development is high-density. That much development on only 10 acres (some of which has a highway running over it), means the project will take a towers in the park style approach.

If you’ve already gotten this far, your next thought might be “...but how did they get through local zoning?”. Well, it’s not because Canadians are all enlightened YIMBYs. When the project was announced in 2019, there was major outcry amongst Vancouver’s homeowner NIMBY set, but it didn’t matter. Legally speaking, Senáḵw is not in Vancouver.3

When the Canadian government returned the land to Squamish control, it passed out of the jurisdiction of the City of Vancouver and into the hands of the tribal government of the Squamish Nation. When the Squamish government decided to develop the land for the benefit of the tribe at large, there was nothing local NIMBYs could do to stop it.

A YIMBY, a Georgist, and a Product Designer walk into a bar

This is the part where most reporting leaves off. It’s a cool story, but the situation is pretty sui generis, so it couldn’t possibly have any implications for policy makers, advocates, or reformers, right?

WRONG

This story has got something for all manner of urbanists. So we’ll take it from the top and start with housing.

The first thing to note is the scale of development.

If we recall our land use economics 101, density is driven by land values. The more expensive land becomes, the more developers substitute constructed square footage for dirt. This is why New York is dense and places in North Dakota are not.4 In the words of Alain Bertaud, density is not a design decision.

The fact that “the market” believes Senáḵw can support the planned level of development means it also thinks the surrounding areas could support greater density as well.5 This should give us an idea of how supply constrained Vancouver's housing market actually is.6

The project’s revenue model is noteworthy as well.

For the Squamish, Senáḵw is a money making venture. Yes, there’ll be some below-market-rate housing, but the development is supposed to both pay for itself in perpetuity and put money into the coffers of the Squamish Nation. And all of this is to be accomplished without sales, income, or capital gains taxes on any of the residents.

Instead of a more standard mix of taxes, the business model will be completely based on leasing revenue. If this sounds strange, it’s more common than you realize. The Boston Planning and Development Agency generates a significant portion of its revenue from developing and monetizing properties it owns. Closer to Senáḵw’s example, the entire Battery Park neighborhood in New York City is owned and administered by the Battery Park City Authority.7 Ciudad Morazán in Honduras is also being built using this approach. Famously, this is also just how a mall works.8

The deeper insight here is how a city’s revenue model shapes its attitude towards growth.

Like we’ve talked about before, municipal governments are in the platform business. They build infrastructure and, if they’re successful, more and more residents show up and help build everything a city is on top. Social media platforms like Youtube or Tiktok are fundamentally infrastructure providers as well. They provide a platform that then requires users to show up and make them what they are.

Critically, though, a platform's revenue model shapes the way infrastructure gets designed. Social media platforms monetize attention so everything is built to further engagement and keep eyeballs glued to screens. The way they make money dictates their design. The same principle applies to municipalities. The way a city chooses to monetize the value it helps create impacts its policies, its politics, and the design of the built environment.

In the case of Senáḵw, because the Squamish are directly monetizing land value through leasing, they’re incentivized to max out development and assume the most pro-growth stance imaginable. Ultimately, Senáḵw is a product and a product’s design is always downstream of the business model.

Outro

Senáḵw is a fascinating project, no matter how you come at it. For a YIMBY, it gives us a glimpse at what’s actually possible in a world with better land use rules. From a Georgist perspective, it will provide another real world example of the benefits of leveraging land values for public infrastructure. And when we zoom in on design (maybe this is for the Strong Towns folks), it highlights the link between a city’s revenue model and the way the built environment develops as a result.

No matter your pet issue or particular concern, if you’re an urbanist of whatever stripe, Senáḵw is a project worth watching and one that I’ll continue following with nothing but the highest hopes.

For non-North Americans, both the U.S. and Canada had similar policies of restricting native populations to designated areas. In Canada, these are called reserves. Canadian reserves are granted some elements of self-governance by Canada’s federal government and while the national legislature could revoke some of those powers, public sentiment is such that this would be politically non-viable.

I say technically because what is or isn’t legal comes down to whatever a judge is willing to decide after the fact.

That said, Senáḵw is contracting with the City of Vancouver for fire, police, utilities, public works, and library services. This is actually a fairly common arrangement (at least in the U.S.) where a municipality on the periphery of a much larger city will simply contract with their larger neighbor for service provision.

Apologies for my non-American readers; a place with low land values and therefore no density (like North Dakota) is going to be — definitionally — some place you’ve never heard of.

To be precise (and pedantic), “the market” in this case is The Squamish Nation, Westbank Projects Corp., and the Canadian Federal Government. We could debate how representative the backers of one project are of the market at large, but there’s some real estate finance guys with spreadsheets doing math based on comps, so close enough.

To clarify, I’m not saying the entire city of Vancouver could support development at the scale we’ll be seeing in Senáḵw; if the entire city allowed for greater density tomorrow, we’d see relatively less intense development spread out over the entire metro.

The Battery Park City Authority is a public benefit corporation that remits excess revenue back to the NYC’s general fund.

For the Georgists in the audience, I hope it’s obvious that Senáḵw is an example of actually existing Georgism, albeit of the Spencerian entrepreneurial community variety (just like Ciudad Morazón in Honduras).

Excellent read!

Nice piece! I saw this going up in Vancouver recently and wondered what it was. The development definitely deserves more attention from urbanists.