How we build housing is how we build the economy

Housing policy is economic strategy

Over the last several weeks, I’ve had great conversations with three different flavors of urbanist: Laura Foote from the YIMBY camp; Andrew Burleson from Strong Towns, and Greg Miller and Lars Doucet, representing the Georgists. In each of these conversations, I asked folks “what they thought was wrong in the world — or at least in the places we live — that’s in need of fixing.” No one had any difficulty providing a response.

At their cores, each of these movements aren’t just about urbanism, they’re about urban reform. And, after some reflection, it actually feels like they’re all pointing at different parts of the same thing. Something is broken and in need of repair. Or maybe wholesale replacement. Some will say it’s capitalism’s rotting carcass we smell. Others will claim it’s neoliberalism (whatever that means) death rattling in our ears. But these prognoses are too abstract for my taste. What YIMBYism, Georgism, and Strong Towns do is tell a story rooted in the material conditions of the places we live. They all point to problems in society and identify their roots in the literal foundations of our communities.

Admittedly, YIMBYism, Georgism, and Strong Towns don’t agree on absolutely everything; and, oftentimes, the things they do agree on they talk about in different ways. But what they all point to is an American economic paradigm that’s coming to an end. The development pattern we relied upon following WWII has run its course. And, as it’s begun sputtering to a halt, the economic prospects for younger generations have gone from bad to worse, imprinting political nihilism and reaction on the hearts of Americans living through the most politically formative years of their lives.

In my mind, this leads to one conclusion: our task is more than making minor adjustments to land use policy; instead, it’s replacing an entire economic model that’s now utterly spent. And, as Laura Foote has said before, we don’t have forever to figure out what comes next.

How We Built the Post-War U.S.

The story of American land use policy starts at the local level and is at various points a tale of our country’s worst impulses. Early proponents of zoning, what we theoretically use to separate uses, were using it to segregate people. After the supreme court struck down explicit race-based zoning in Buchanan v. Warley, early nativist reactionaries (of which there were many) adopted modern zoning as facially race neutral policies to achieve the same outcomes. This approach was deemed acceptable by the high court’s 1926 decision in Euclid v. Ambler, enshrining zoning as a permissible exercise of the state’s police power.1

While the judicial system was busy determining the legal limits of local land use regulation, the federal government was busy shaping housing markets as well. In the late 1920s, the Department of Commerce released multiple pieces of model legislation to encourage the adoption of zoning across the nation.2 Technical assistance was only the beginning, though. The federal government’s real impact came when it started physically reshaping the country via the credit markets.

In 1934, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) began insuring private mortgages; critically, it only insured mortgages made (a) to white — or at least not black — families and (b) for single-family homes in low-density suburban development. These guidelines reshaped the mortgage industry by giving lenders a “de-risked” financial product and paved the way for 30-year fixed rate mortgage, a financial instrument some have called an abomination before the eyes of the lord.3

Later in 1938, Congress went beyond insuring private mortgages and created Fannie Mae to actually buy them off the books of lenders. Having a guaranteed buyer for mortgages allowed lenders to recycle capital faster and issue more loans. Critically, Fannie Mae was only buying mortgages that already qualified for FHA insurance; even as the federal government was injecting capital into housing markets, it was only available for suburban development and with the same racial qualifiers attached.

As we near the end of WWII, the foundations for the post-war development model were well laid, but there was still more to be done. After all, a couple single family homes does not the suburbs make. We also need car culture.

The Federal Highway Act of 1956 created the federal highway system we all take for granted today. Government support for explicitly car-centric infrastructure opened up land around the country’s existing urban cores. While all this financial alchemy was summoning a new world into existence on the peripheries, much of the old world was razed at the same time. Neighborhoods in the urban cores were seized through eminent domain and replaced with highway interchanges to connect central business districts to the newly risen suburbs.

I want to highlight here that all of this land use policy isn’t just land use policy in some narrow sense. Easy credit, subsidized car infrastructure, and the imposition of restrictive zoning narrowed the aperture of what types of development was legally permissible and then put a finger on the scales of what was financially feasible — all in the service of promoting homeownership nationwide.

Homeownership became mythologized as the pathway to economic security and an important milestone in the life trajectory of every would-be middle class American. As long as the economy always and everywhere grows, housing prices would only ever go up; so all we needed to do was help every successive generation get a stake in the ground (no pun intended, maybe).

To commandeer an old line from a different context, show me your land use institutions and I’ll tell you your development strategy.

The System Was Always Extractive

The American development model we created over the course of the last century left much to be desired. Sprawling, car dependent development makes our communities difficult to navigate for the young, the old, or really anyone not able to drive a car. Car dependency also introduced vehicle emissions that contribute to asthma and cardiovascular disease. And that’s on top of tens of thousands we lose every year due to motor vehicle fatalities.

But maybe car culture was a necessary evil. We needed the car to get to the suburbs, we needed the suburbs to enable homeownership, and we needed homeownership to launch the middle class. So, there was a system that came with some tradeoffs, but — at least for a while — it worked. Right?

I don’t think it actually did.

And to better understand why, it’s educational to take a closer look at the communities this system never served at all.

Like we’ve already said, access to subsidized mortgages was gate kept on the basis of race. From 1930 to 1960, 98% of all federally subsidized loans went to white families. And while the system was broadly prejudicial against anyone not considered white by standards of the times, conditions were especially bad for Black Americans.4 For example, Black homebuyers weren’t just relegated to more expensive uninsured mortgages; instead, they often had to resort to something called a land installment contract. These financial instruments looked and smelled like a mortgage, but allowed the lender to fully repossess the borrower’s property in the event of a single missed payment. If a family was late on their final payment — even after years of timely payments — they’d forfeit their property (incentivising lenders to sometimes “lose” a check in the mail).

At the same time as folks were excluded from cheap credit for new homes, their existing communities were also literally bulldozed. All those highways connecting suburbia with preexisting urban cores had to run through somewhere and somewhere usually meant Black neighborhoods like the Fillmore District in San Francisco or parts of Tremé in New Orleans. Displaced individuals then ended up in ill conceived federal housing projects like Pruitt-Igoe which accomplished little more than warehousing working class Black folks in conditions of concentrated poverty.

The communities that did persist in places like Harlem didn’t fare much better. From Daniel Wortel-London’s The Menace of Prosperity:

Four-fifths of Harlem’s commercial and residential properties were owned by non-locals or companies by the 1960s. Four-fifths of the Harlem workforce was employed outside the community … This dependence reduced the economic function of Harlem and other “ghettos” to providing revenue and low-skilled labor on behalf of outsiders.5

The post war development was extractive from the jump. And although that’s easiest to see in the context of racial discrimination, it also create an inter-temporal system of wealth transfer that’s slowly grinding to a halt.

The Ratchet Effect

Workers benefiting from easy credit and an invitation to the party that was The Golden Age of Capitalism turned their earnings into homeownership. When the value of these homes outpaced inflation, however, that wasn’t because their owners were keeping the finishes in the kitchen up to date. It’s because earlier waves of homebuyers were able to extract larger and larger shares of economic growth from the cohorts of homebuyers that followed.

Now, pundits (myself included) like to point to the run up in Bay Area housing prices following successive tech industry expansions as a go-to illustrative example. The easier place to see the inter-generational wealth transfer, though, is in Los Alamos, New Mexico — home of Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL).

From my my post on the housing crisis in Los Alamos:

When the federal government pours money into LANL, that money covers payroll, and that payroll gets spent on housing, which pushes prices up. As long as supply remains inelastic, more money just means more problems (higher prices).

To clarify, some of those thousand [new] hires will be backfills for retiring employees, not net new headcount. So maybe it’s slightly less bad than it sounds? Sadly, no.

The marginal retiring LANL employee doesn’t automatically free up a unit of housing upon retirement. Chances are they bought a home at the beginning of their career with the lab; so when they retire, they’ve paid off a $350k mortgage on a house now worth $600k. The replacement hire faces that $600k price tag on a starting salary. And herein lies an important part of the problem: every subsequent cohort of LANL employees has exerted a ratcheting effect on the region’s home prices. We can’t spend our way out of this problem.

As Los Alamos goes, so goes the nation — and that’s the crux of the issue. The country’s development model was based on a land use system that, by its construction, would only ever work for some and could never work forever.

How Things Fall Apart

What does the system look like as it’s running out of steam?

For starters, our once exceptional labor mobility has nearly disappeared. According to Yoni Appelbaum, at our peak, as many as 1 in 3 Americans moved every year; that figure is now closer to 1 in 13. At its core, this is about housing costs. We used to move toward opportunity, now we move away from cost.

After we decided we’d no longer allow cities to build up or fill in, we began dealing with housing costs by sprawling out. Drive-until-you-qualify, however, has become increasingly ineffective. As Andrew Burleson points out in The Geometry Problem, linearly increasing sprawl non-linearly increases traffic. This is how we get soul crushing super commutes and why everyone’s suburban drive to Costco goes from 10 minutes to 30 after only a modest amount of local growth.6

To borrow slightly different framing from Lars Doucet: America has always been a frontier economy, suburban expansion was our last last frontier, and that frontier is now used up. Barring the miraculous invention of some personal conveyance not bound by the strictures of either terrestrial geometry or energy costs, just doing more of the same harder will not carry us through the rest of the century. And when an economic system stops delivering on its promises, the consequences aren’t just economic.

Our culture and politics are always downstream of material conditions. Those conditions also exert an outsized impact on us as we live through our most formative years of young adulthood. The generation coming of age right now isn’t just experiencing a housing crisis—they’re having their baseline expectations about what’s possible shaped by a system that’s grinding to a halt.

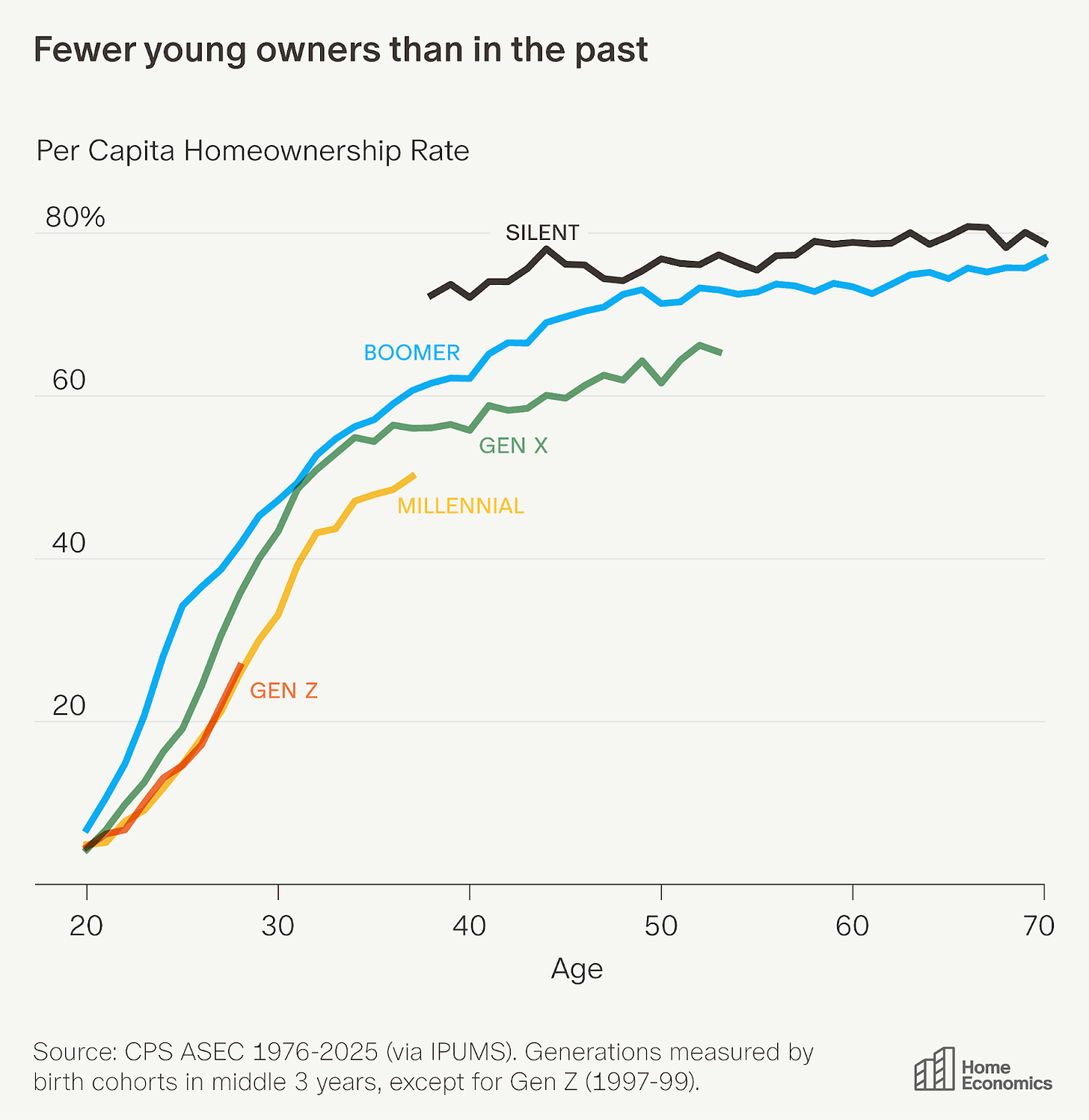

Gen Z is doing about as bad as Millennials in terms of homeownership rates. And before we get into all the revealed preference whataboutism, a 2025 survey reported that 90% of Gen Z would like to own a home; only 62% believe that will ever actually happen. No wonder we see political fatalism and cultural nihilism.

Moreover, the point here is not that we need to get homeownership rates back up. It’s that we have a system that defines material success as achieving homeownership and this system is now failing on its own terms — and that failure is being felt hardest by everyone under the age of 40.

The Revolution Will Be Urbanized

If it’s not obvious by this point, I take a pretty materialist view of politics, culture, and society. And based on the last couple paragraphs, it might seem like I’ve succumbed to the same fatalism and doom I just spent a hundred words pointing out.

Believe it or not, I’m keeping hope alive.

Yes, things are breaking. But I think the grinding gears of our economic system are exactly what gave rise to the three reform movements that prompted this reflection in the first place. Strong Towns got started in 2009. YIMBYism took off in earnest around 2014. And Georgism…well Georgism has been politically dormant for ninety-years, but the fact that it’s now reawakening like one of those hibernating African fish makes my point all the same. Our social universe is downstream of material reality and material reality is driving us to grapple with the question of what comes next.

To put a finer point on it, my optimism comes from all the ways these three urbanist tendencies overlap. And that’s not just on theory or policy goals. All the most serious folks from each of these camps share a broadly liberal world view. Everyone wants to move in the direction of a world where the material necessities are easily accessible and people are maximally enabled to author the stories of their own lives. Similarly, there’s agreement on the stakes. It’s not about getting a couple extra bike lanes; it’s about refactoring the substrate of our entire economy and, in the process, leaving future generations with institutions capable of delivering material prosperity. It’s a tall order. But many hands make light work and, given the hands already set to the task, I remain optimistic that we’ll succeed in building that better future.

This is where we get the term “Euclidean Zoning”.

In 1922 (prior to the Euclid decision), the Department of Commerce created the Standard State Zoning Enabling Act (SZEA); this model legislation served as a blueprint for state legislatures interested in explicitly granting their local governments legal authority to regulate land use. The department followed up in 1928 with the Standard City Planning Enabling Act which elaborated on the technical guidance provided via the earlier SZEA.

It was me.

American land use policy was, and to a great extent still is, prejudicial along lines of race and class. This includes everything from the seizure of treaty lands from native Americans to the burning down of West coast Chinese communities by xenophobic arsonists. In service of this essay’s larger point, I stuck with the most explicit examples of exclusionary policy, hence the partial telling.

The Menace of Prosperity, pg. 183

Technically, NIMBYs complaining about increased traffic from denser housing have correct intuitions here. More housing often leads to worse traffic given the way we’ve built existing communities. For the standard American suburb, there’s an awkward middle level of density where car traffic is bad, but mass transit is not quite effective. For more on this topic, see Andrew Burleson’s The Missing Middle of Transportation.

Hey Jeff, great post. It's pretty wild how our built environment affects the economy in different ways. The contrast between my current home in Albuquerque and the place I lived in Spain tells the story.

I live in a small historic neighborhood near Downtown Albuquerque now. There are remnants of old corner convenience stores, pubs, pharmacies, and grocery stores lining the now-dormant Mainstreet and surrounding area. We also used to have a rail yard where many of the locals worked. The start of the neighborhood decline correlates with the decline of the Rail Yards and the construction of the interstate system that destroyed historic neighborhoods in Albuquerque. Today, I have to leave my neighborhood to purchase anything outside of New Mexican food. The Mainstreet is dead, few locals have jobs in the neighborhood, and the streets surrounding my house serve mainly as a throughway for commuters.

Spanish cities have a diverse array of small businesses on every street corner in every neighborhood. There are so many random small businesses that sometimes it's hard to believe how they've stayed open so long. I stand to believe the success of small businesses in Spain, and other densely populated regions, is walkability and a competitive framework that the Spanish built environment creates. Every neighborhood in Barcelona has several pharmacies, cafes, print shops, grocery stores, pubs, and more creating a competitive, small-scale environment for small businesses to thrive. Plus, you get jobs for locals.

When we build our cities around getting between big box stores and the suburbs, we shift the advantage to big corporations and wealth consolidation. If the US were to ever get serious about saving Mainstreet America, one first big step would be allowing more people to live near Mainstreet.